Food courts are likely never to be the same again. What’s the future? The ‘street restaurants’ – those outside shopping centres – have adapted; they’ve embraced take-away, reconfigured their seating areas and shortened their menus… But food courts are different; the challenges are more intense. Francis Loughran explains…

Food and hospitality’s revival in shopping centres is going to happen, but not if the strategy is simply to wait for customers to come through the door. COVID-19 has compressed the evolution of consumer behaviour from five years to three months. What we would have been planning to do by 2025 has to be done today. Is your shopping centre prepared to capture the opportunities created by the new landscape?

Shopping Centres have been hampered because the creed of ‘Eat Local’ seems to have somehow excluded Shopping Centres from the definition of ‘local’. This seems to us to be a significant and important call to action:

Why are shopping centres not being drawn into the ‘Eat and Support Local’ campaigns? How has the industry allowed itself to be portrayed (albeit indirectly) as not being ‘local’?

We are at the beginning of a new future and malls cannot expect to pick up where they left off and, as such, it would be a mistake to look to the lessons from the GFC. At that time, Takeaway Food Services (as the Bureau of Statistics likes to call the QSR sector) never had a month of negative growth, while cafés/restaurants experienced only a slight decline in turnover. The bounce-back was strong because consumer fundamentals were shaken, but not stirred – unlike today.

Customer expectations towards F&B have changed because spending on F&B in shopping centres has become more discretionary and less reliable. Shopping centres need to change as well – it’s a ‘Blue-Sky Opportunity’.

Many, if not most, people will revert back to their comfortable habits as soon as possible but we should not be lulled into complacency by this. The following example shows why.

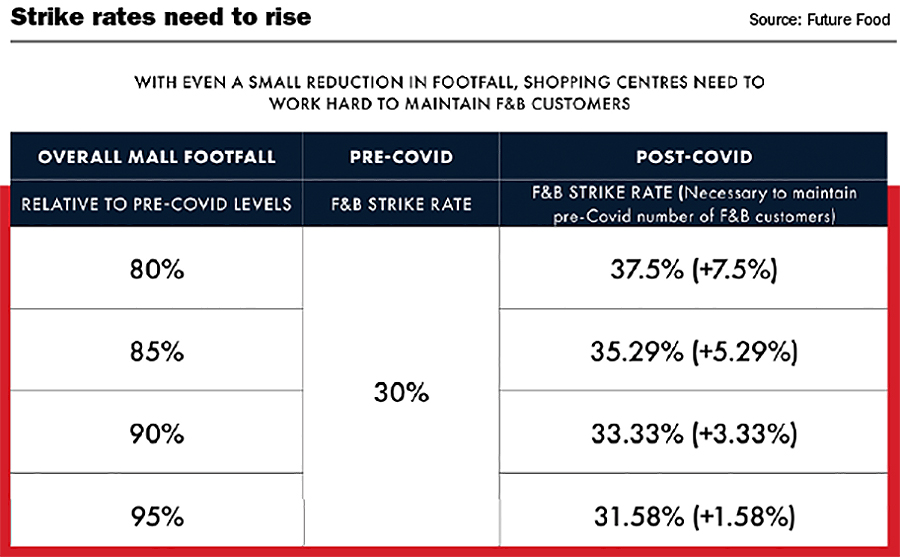

As I write this (mid-July 2020), footfall data for Westfield Warringah on Sydney’s North Shore was at about 80% to 85% of pre-pandemic levels. This is an excellent recovery result, but let’s take a look at what this means for F&B. If the mall’s F&B strike rate was originally at 30% (three out of ten visitors spent money on F&B,) then to maintain the same number of customers, the strike rate would have to increase to 37.5% (see table below).

We should not underestimate the magnitude of change in consumer behaviour necessary to achieve these results. This is especially true in light of the surge in online spending across all sectors of retail. The latest figures show that 11.1% of total retail spending was done online. This is up from 7.1% in March 2020.

We would have expected this evolution in online retailing to have taken place over the next several years. Instead, we are dealing with the future now.

While all states and territories are at varying stages of their recovery trajectory, it is critical that all shopping centres, large and small, place a new lens on the expected standards for F&B in their food courts, entertainment precincts, restaurant clusters and standalone F&B retail tenancies. Owners and landlords must ensure that they are seen as the new face of hygiene, cleanliness and compliance to attract customers back to spend, dwell and socialise.

Combined with the myriad efforts from food operators, this partnership can maximise operators’ turnover and thus provide sustainable rental income. This means that we must give greater reasons for customers to engage, and to recognise that hygiene and safety have become marketable commodities and drivers of F&B footfall.

Steps to the next normal

Jay Reiner, the UK food critic for The Guardian, has said that starting up a kitchen again is easy but that, “Reigniting the buzz in the age of social distancing may prove an awful lot harder”. This is echoed by Justin Hemmes of the Merivale Group and the CEO at Australian Venue Co, Paul Waterson, two of the leading restaurateurs who were at the forefront of the F&B revival. They understood that, while core principles were unchanged, they were starting up new businesses in a new environment, which required a lot of planning and new processes.

For shopping centres the key principles are that: A) Revenue is the driving force behind rent, B) F&B is a key component in evolving malls into lifestyle centres and C) F&B is an asset category. F&B has grown as a percentage of turnover (MAT) during the past 20 years and has been the cash cow for increased hours, food and entertainment in a family friendly environment. It is in the interest of the asset as a whole that F&B gets kick-started and moves beyond the basics.

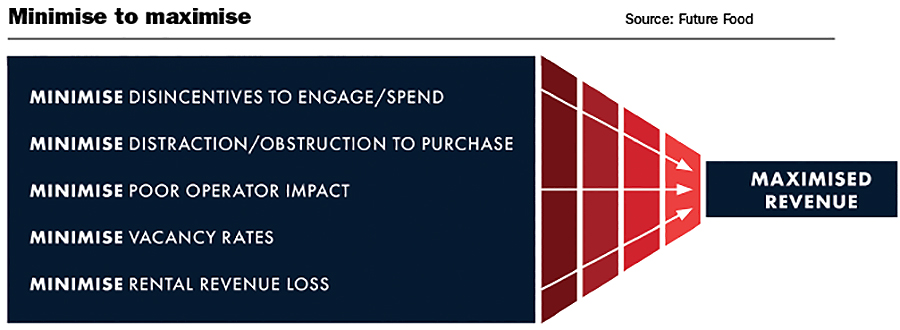

F&B revenue maximisation (and thus rent stabilisation) is subject to a number of interconnected initiatives:

1. Embracing online sales:

a. It is important to work with, not against, the impact and the changing habits of consumer behaviour.

b. Facilitating ways for centres’ food operators to process delivery orders. If customers don’t want to go to the mall (for whatever reason), it is important to figure out how the mall can go to the customer.

2. Increasing the strike rate by providing a positive experience:

a. This is more than just having great food.

b. Communicating and marketing clear signals that reassure your customers they are going to be looked after properly by your food operators: menus and ordering app available on centre website, information about whether pre-payment is required and if there is a time allocation (60 / 90 / 120 minutes) per table and all of the distancing and hygiene measures taken by the operator.

3. Getting the shoppers who are cautious about life to come back to their pre-COVID habits:

a. While the majority of people are keen to get back to their previous habits, there are significant numbers of customers who won’t or can’t, due to concerns about safety and/or money. Thus the trajectory of the recovery will initially be steep, but will have a very long tail to get back to where we were at the beginning of the year.

b. We believe that people will go back and spend if the platform of readiness gives them confidence.

4. Empowering centre management to demand standards from their retailers:

No dirty floors, no un-bussed tables, clean sightlines into tenancies, empty full rubbish bins, lean uniforms, no clutter or possibility of cross contamination and generally upholding professional food and beverage presentation standards at all times.

5. Making poorer operators elevate their standards:

a. Revisit the F&B mix: Do we need to retain these operators? Do we replace, or do we refresh?

b. Are the food operators relevant to the local market?

c. Can the operators be taken on the journey? Are they worth it for the landlord to invest in (time, effort, hygiene, etc.)

6. Getting the critical mass properly balanced:

a. Are there enough local and/or independent food operators?

b. Is the F&B mix in a particular centre distinguishable from other malls in the portfolio?

7. Landlords taking a holistic view: The totality of the food offer and the environment has overriding messages and planning.

a. Each F&B operator at the centre is presented with a uniform code of conduct. This can’t be left to the individual operators but must be driven by centre management.

b. Having centre-wide management of pedestrian flows and social distancing.

c. Subsidising and encouraging promotions to entice customers to come to the centre.

d. Visible Hygiene Officers that enforce all safety measures and are also responsible for wiping down and sanitising public areas.

The task ahead

We recognise that shopping centres are essentially safe public areas, but that is not enough to win over the significant portion of former customers who are nervous about being out of the house to come back to centres and restart their shopping and eating habits. We are in the Next Normal and this requires delivering a next level of standards in order to provide new customer experiences.

Food courts present shopping centre owners with a distinct ‘blue-sky opportunity’ which requires maximum landlord effort. Operators in the food courts have been more affected by the COVID-19 lockdown than those across the balance of the centre or on the high streets: Individual F&B outlets have been able to create their own vibe and energy.

• Food court tenancies lost their ability to effectively service their customers because their seating was eliminated and delivery services were, and are, constrained.

• The industry-leading innovations in F&B have been led almost exclusively by non-centre retailers.

This presents a distinct opportunity to reposition F&B in centres as being made up of many locally owned small businesses that are family operated.

Individual centres need to connect with the local community and ensure that their properties are not being overlooked, as all consumers are trying to support small business as a way of keeping them afloat during these challenging times. We need to promote our local food heroes in our local centres.

The ROI: principled partnerships prepare proprietors

The bottom line is that without these measures and these partnerships, food operators may have a difficult time in maximising revenue and thus returning to profitability. We have analysed a typical F&B outlet and have calculated the returns.

As the chart (top right) shows, this Next Normal does not entail simply cutting rent. The return to pre-COVID profitability for the average F&B operator requires a coordinated response that includes increased centre hygiene and coordination of customers along with operator investments in technology and a realignment of labour and menus.

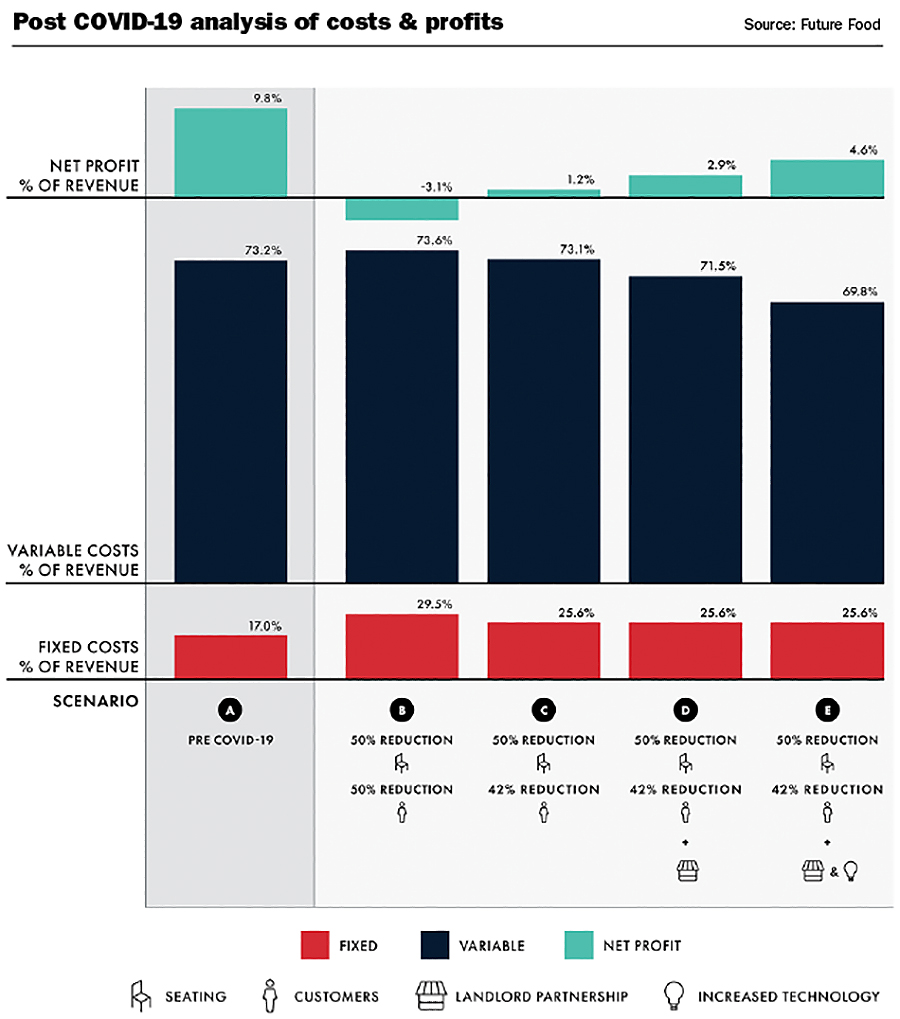

Column A reports on the benchmark figures for a food operator pre-COVID. While margins were relatively small, an average operator was able to survive.

Column B shows the profitability effects of the ‘do-nothing’ strategy: Follow regulations and guidelines, but otherwise go about business as usual and hope. Clearly this is not a sustainable path.

Just as importantly, the economics for an average F&B outlet are such that it may be problematic to get funding for new ventures. This would mean that F&B vacancies would be significantly harder to fill.

Column C shows that a food operator can return to profitability (just) by being proactive with marketing and communication to increase customer flow and thus turnover. However, this is more akin to surviving than thriving.

Column D shows the positive effect that landlords can have on the profitability of their food operators by implementing many of the steps that we have outlined above. It is important to emphasise here that a Landlord Partnership with food operators is about investing in the holistic customer experience.

It is about creating and communicating healthy environments. It is about the breaking up of common area seating to create more individual areas that don’t feel like your neighbours are breathing on you. It is about a coordinated effort in considering where food fits into the picture as retail and entertainment come back.

Finally, Column E shows how retailers can leverage the Landlord Partnership with investments of their own – contact-less ordering, software to aid in procurement and staffing, re-engineering kitchens to facilitate distancing and safety. The Landlord Partnership plays a vital role as, without those measures, food operators would not have the security or the cash flow to invest.

The net effect of this coordinated response on the part of landlords and operators is gradual return to profitability, even in the face of distancing regulations and reduced numbers of customers. As more regulations ease and consumer anxiety abates and incomes rise, F&B operators can see a path towards returning to pre-COVID-19 benchmarks. Without this collaboration, we see a much more difficult path to turnover maximisation and therefore sustainable rental revenue.

To summarise, never before have F&B operations had to work as hard on safety and hygiene all the while still remembering that they need to give customers the best experience they can.

We started off by making the claim that the future of five years from now is here already. Before the pandemic, some malls were already thinking about the Next Normal. Westfield, for example saw that its centres would turn into Lifestyle Centres. What we need to incorporate into our strategic thinking and planning is that consumer lifestyles now more closely reflect what would have happened in five years’ time without the pandemic.

Westfield 2025 vision

Without engaging with all customers, not just those first movers eager to get back to the way things were, shopping centres will not be able to offer a lifestyle experience for everyone.

The Next Normal in F&B in managed shopping centres requires landlords and operators to work together to create an environment that is not just safe and hygienic, but one that also is seen to be such. There is significant latent demand for shopping centre F&B, but food operators in malls, especially those in food courts, are starting from a position of relative weakness and need a coordinated effort from all stakeholders to regain their premier positions. This is far from an impossible task and we look forward to tackling the challenges ahead.