This is a really great insight with figures to back it up, as to why the shopping centre industry in Australia is the best in the world. It’s an article that compliments the JLL report in this issue.

Tony Dimasi looks at the resilience of the Australian shopping centre, examining its performance for almost a quarter of a century.

I have remarked in various forums over the past few months that, in overall terms, I consider the retail sector in Australia is looking as healthy and well placed as it has at any time over the past eight years, i.e. in the post-GFC period.

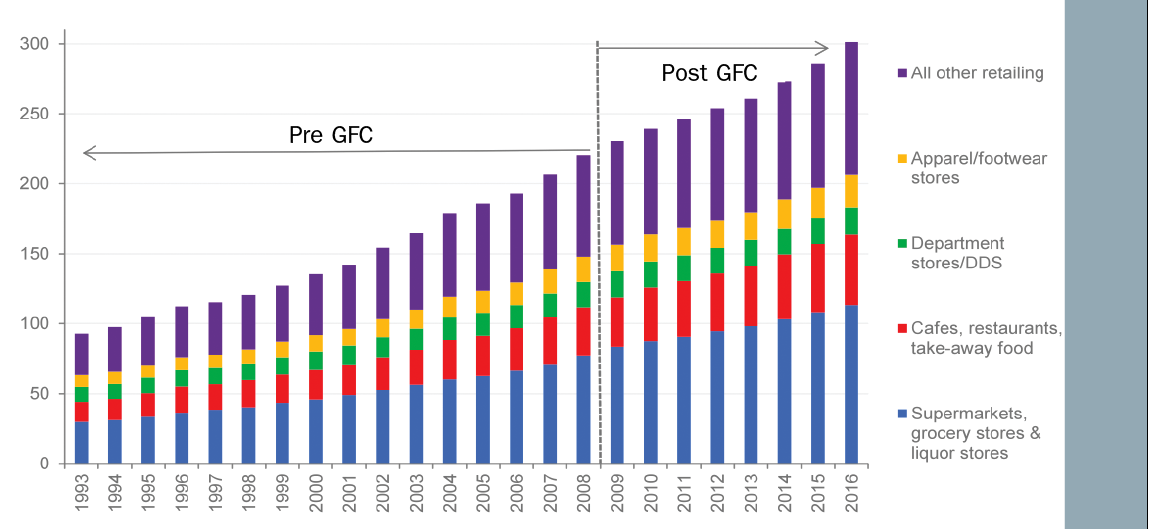

By no means is it all a bed of roses. Retail trading conditions are still patchy at times, both across geographies and categories, and many retailers remain reluctant to commit to new store opportunities, making leasing conditions for owners/developers considerably more challenging than they were for many years prior to the GFC. However, if there is one word which I think can describe the Australian retail sector, that word is ‘resilient’, as Chart 1 shows.

- Chart 1: ABS Retail Trade – Total Australia (FY1993 – FY 2016), $ billions

Amazingly, in the eight years following the GFC retail sales growth in Australia has averaged 4% annually – and that result has been achieved in an environment of almost no retail inflation, particularly over recent years.

That 4% growth is only 1.9% lower than the long-term average achieved in the sustained period of growth for the Australian retail sector from the early 1990s to 2008.

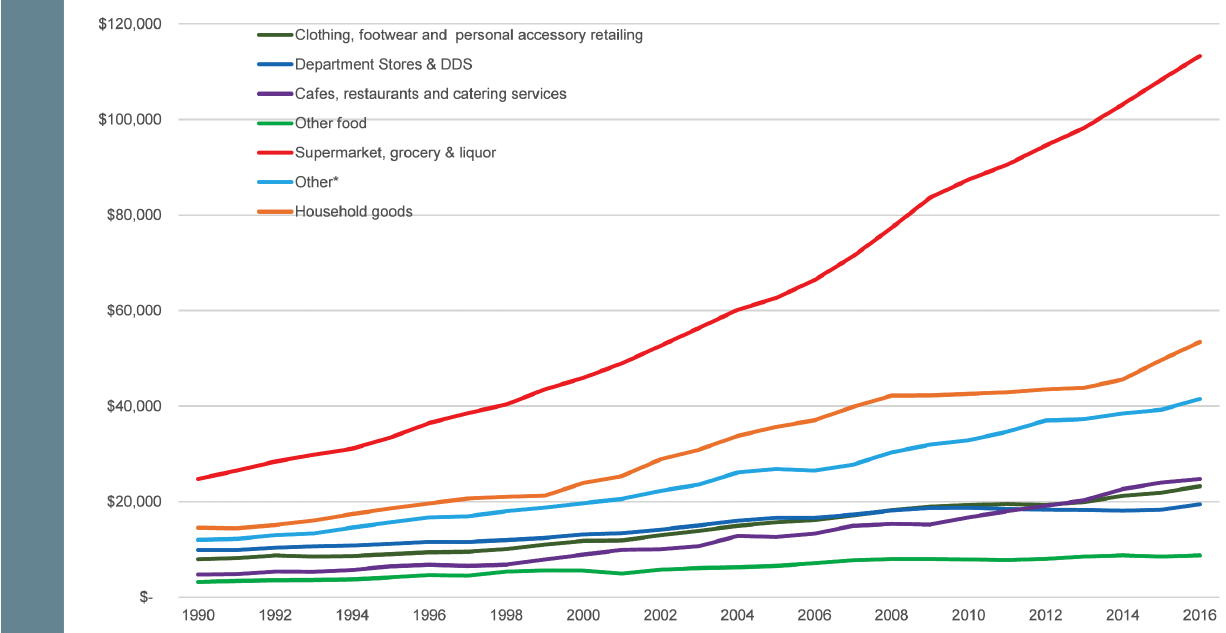

Across retail categories, as shown in Chart 2, the inexorable growth of the supermarket sector over the past quarter-century is the most clearly evident trend, while long-term growth in household goods spending is also readily apparent, albeit dampened for about five years following the GFC.

What is somewhat less apparent, but of great significance, is the fact that spending at cafés and restaurants is now higher than either spending at department and discount department stores (combined), or spending at clothing, footwear and personal accessories stores. If we go back to 1990, spending at cafés and restaurants was less than half the levels recorded at either of these two store categories. That transition of spending, and the related changes in shopping needs and expectations, go a long way to explaining why we are seeing the emphasis on take-away food, cafés and restaurants in our shopping centres on the one hand, and the rapidly reducing influence of department stores, even discount department stores, on the other.

The rate of growth in retail sales would have been higher over recent years but for a number of important factors which have contributed significantly to deflation in key categories – particularly in apparel and supermarkets. Intense levels of competition between Woolworths, Coles and Aldi have contributed significantly to the subdued growth in supermarket sales in 2015, and all expectations are that this trend will continue for some time yet. In apparel, significant deflation as a result of ongoing innovation in manufacturing and logistics, as well as the entry of new global retailers and the repositioning of Kmart’s offer, has also meant that while the numbers of units sold in many cases has increased substantially, the top-line revenue has not moved to anywhere near the same extent.

- Chart 2: Retail trade growth by category 1990 ‚Äì 2016 ($’000)

Across categories there is still some patchiness in retail sales, but one of the positives emerging over recent months has been the renewed growth in two key non-food categories – apparel and household goods – which suffered the most following the GFC. The growth in those two categories, especially given the deflation in apparel, is particularly important for the larger shopping centres in Australia. Australia’s retail-focused REITs reported comparable specialty MAT growth of around 5% year on year for the first half of FY16.

The emerging growth in these key non-food categories, particularly apparel, is especially heartening, because it is now occurring in an operating environment for Australian discretionary retailers which is highly, and increasingly, competitive, and the best Australian retailers are more than holding their own. Competition has increased obviously from online sales, but even more directly from the bricks-and-mortar presence in Australia of the big global brands including Zara, H&M and Uniqlo. The anecdotal evidence has been that the Australian fashion retailers which have adapted their business models to the new competitive environment are growing sales strongly, while unfortunately a number of others have exited the market or are struggling for growth.

There can be no doubt that the direct entry of the huge global fast-fashion brands has contributed enormously to the renewed excitement in Australia’s major shopping centres, as it has been one of the pillars underpinning the recent and current round of redevelopment, expansion and modernisation. At the same time though, it is also likely that not all of these new international arrivals will end up with highly successful operating models in Australia.

While a few of these international retailers, Lululemon, Zara and Uniqlo among them, have already opened a substantial number of stores in Australia, their plans suggest that there are still many more to come, with the roll-out plans on average about half-achieved across the board.

If we look at Australia’s economic fundamentals, and despite numerous global distractions over recent years – such as the Greek financial crisis, the threat of slowing growth in China, Brexit, etc – the overall picture is sound, thus there should be no real surprise that the retail sector continues to perform steadily. At present, GDP growth is running at around 3%, inflation is less than 2%, and unemployment is in the 5.5% – 6% band. Official interest rates are now below 2%.

Nowhere is the resilience of the retail sector more evident than in the demand for, and the completed transactions of, Australian shopping centre assets.

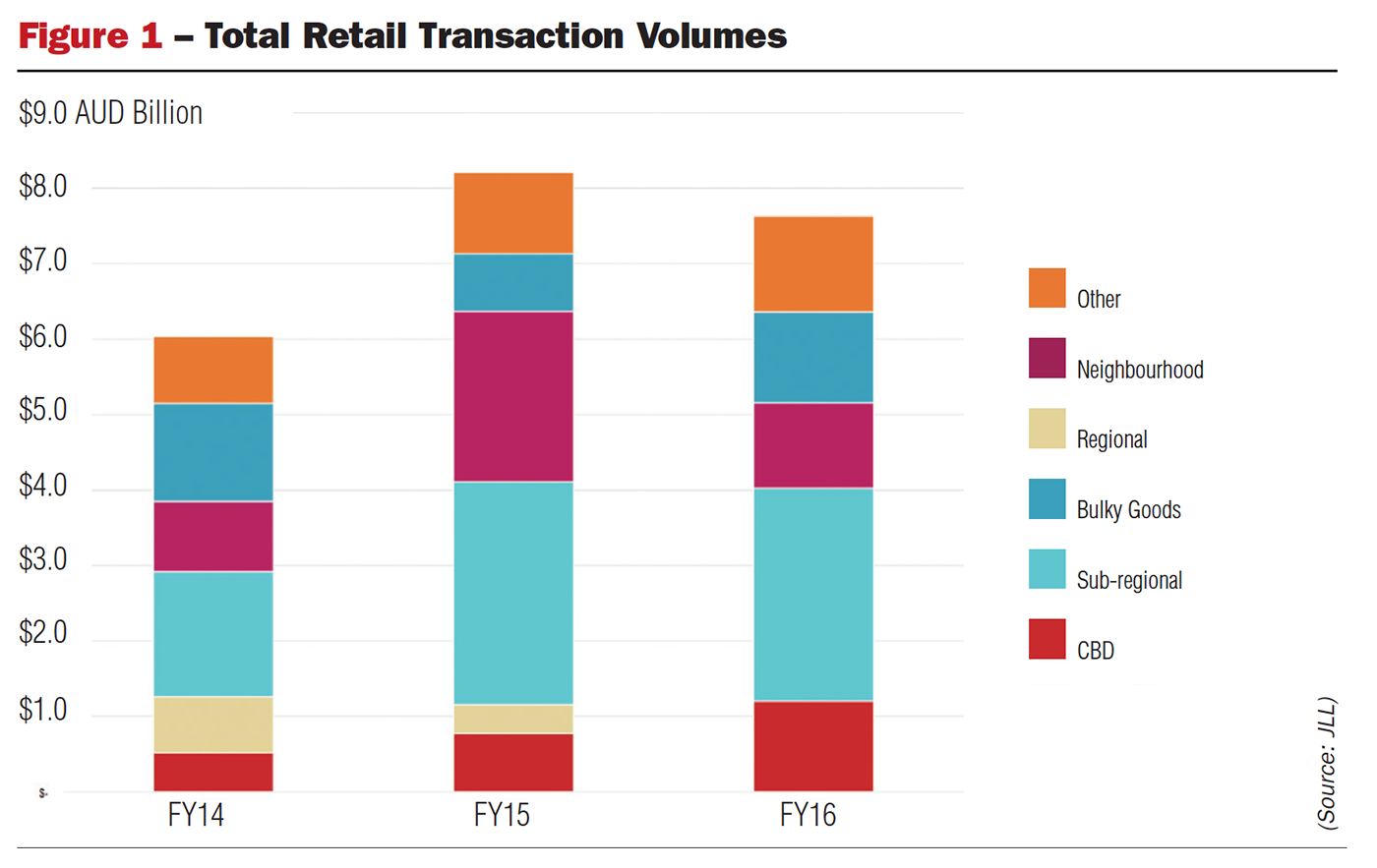

Research available from major investment houses such as Goldman Sachs and Macquarie shows that cap rates for Australian retail assets are now at an all-time low, sitting at around 5% or marginally lower for the best quality regional centres. In 2015, $8.4 billion of transactions in retail assets was reported in Australia – an all-time high. The main purchasers were offshore buyers, superannuation funds, and unlisted funds. Yields compressed significantly as a result, however, the yield range between the better-quality and lower-quality assets remains in line with its long-run average, as investors are increasingly sophisticated and aware of the need to price in risk for lower-quality centres.

All of this demonstrated resilience has meant that Australian retail property continues to represent relatively low earnings risk as compared with most other asset classes. The mantra with retail assets continues to be that every centre needs to be looked at on its merits of course, but the broad outlook for Australian shopping centres continues to be generally very healthy.SCN