How have shopping centre yields compressed during the past eight years or so? How many stores have closed through major retailer collapses over the same period? Do you know the amount of retail space shopping centres comprise, as a percentage of total retail space in Australia? These and other staggering statistics follow. Do they provide an indication of future trends? You be the judge!

As the dust settles on the end of the ‘teens’ decade, the contrast between the start and the end for retail leasing in shopping centres could not be more pronounced.

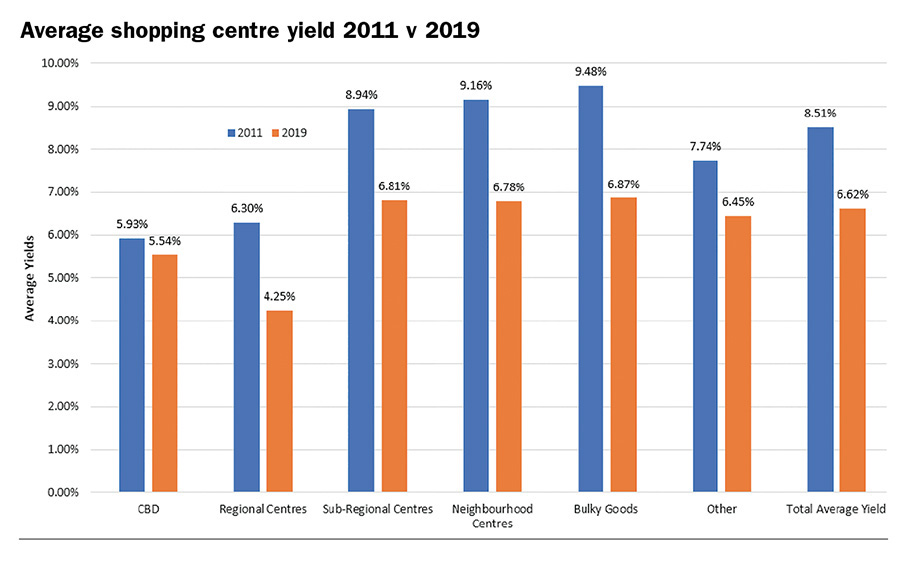

At the start of 2010, Kevin Rudd’s ‘Cash Splash’ triggered an appetite for the expansion of retailers’ store footprints. Landlords were equally optimistic, as post GFC, shopping centres were perceived as relatively safe havens and this started a compression in yields in Australian shopping centres, driven by the weight of cheap money, growing investment demand and a focus on growth assets. As a result, in the last decade, yields compressed across all shopping classes by an average of approximately 200 basis points, similar to the reduction in bond yields.

This injection of capital into the shopping centre sector also triggered a massive level of retail shopping centre expansions in the form of redevelopment, expansions and new greenfield developments. This followed the trend in the US and the UK, which saw even greater sector expansion.

The average annual compound growth of shopping centre supply in Australia throughout the past decade was somewhere in the order of 5% per annum. During the same period, according to the ABS, total retail sales grew by an average of just 3% per annum.

Despite the growth in supply of GLAR per capita, this benchmark is still significantly below the US comparable measure.

Meanwhile, on the demand side, retailers’ have lived through unprecedented changes throughout the past decade. In 2010, online sales represented just 4.9% of traditional retail spending; by 2019 it rose to about 9% of the traditional bricks-and-mortar retail sector, with estimated future growth of 15% per annum.

In addition, local competition increased markedly as a result of increased retailer supply, firstly from domestic retailers’ expansion drive and then from a wave of new offerings from global mega-retailers such as H&M, Zara, Uniqlo, Costco and ALDI, who took meaningful chunks out of local retailers’ volumes and compressed margins.

Then Amazon hit our shores in late 2017 and ramped up a nascent pure play online retailer category, which had previously only included smaller players such as The Iconic and Net-a-Porter.

Over the past decade, consumers have changed their shopping habits dramatically, spending considerably less on discretionary retail in favour of experiences and take-away food. Black Friday and Cyber Monday have changed the timing and disrupted the retailers’ traditional sales cycle.

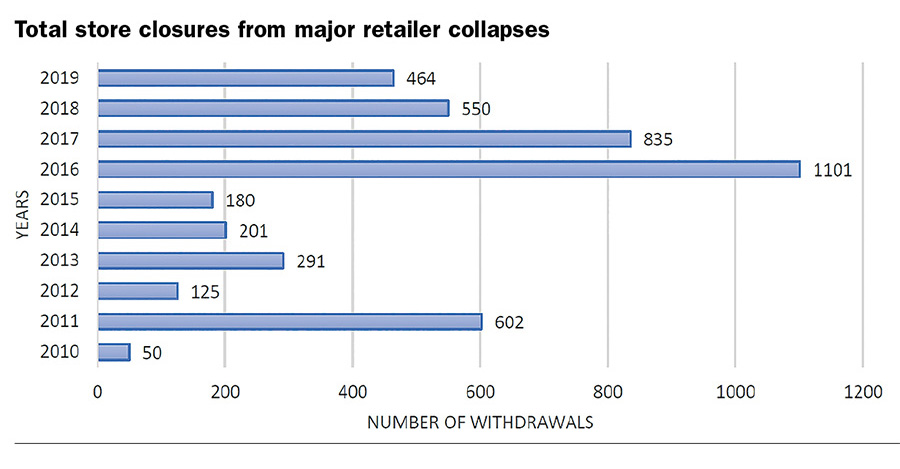

All these factors, combined with very low wages growth and sluggish consumer demand, resulted in an unprecedented wave of retail collapses, which is still playing out today with approximately 170 stores already slated to be closed in the first months of 2020. This trend will likely continue for some time in the current low growth environment.

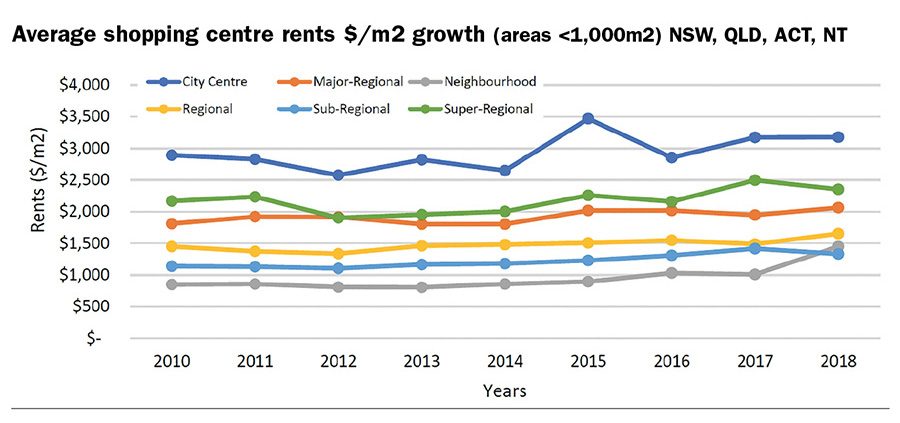

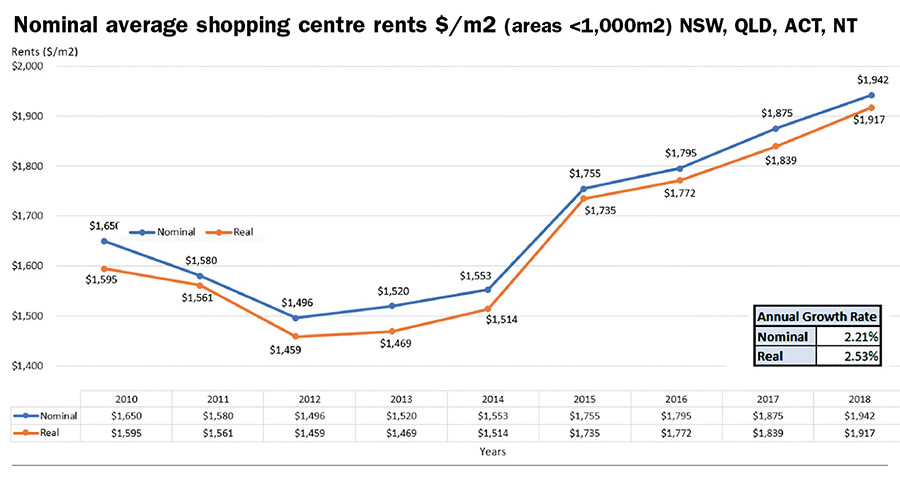

Interestingly, an analysis of Leaseinfo’s database of more than 80,000 retail leasing transactions revealed average specialty shopping centre rents/m2 (which is a combination of renewals and new deals under 1,000m2) followed a similar trajectory to retailer average sales growth in nominal terms over the last decade at an average growth rate of approximately 2.2% per annum, below retail sales growth.

So, what then of the future decade to come? Despite all the recent doom and gloom, to paraphrase Mark Twain “the rumours of the demise of retail and shopping centres have been greatly exaggerated”, for the following reasons:

• A recent opinion piece in Inside Retail Asia states that Millennials and Gen Zs are much more likely to do instore shopping then Gen Xs which means, as their incomes grow, shopping centres will benefit.

• Australia is a hot (and arguably getting hotter) country. Shopping centres provide respite, which causes the dwell factor, which leads to increase spend.

• Australian population growth is increasing at the highest rate in the OECD, with the majority of this growth coming from Asia, where shopping centres are a way of life.

• Shopping centres will continue to evolve to provide much greater in-store experiences and will include a range of new inclusions such as medical, well-being, entertainment, education, childcare, community and even business spaces.

• Retail planning laws in Australia, unlike the US, will continue to protect the incumbent shopping centres from rampant new development over expansion.

However, the next decade will likely be considerably different to the last one. There will be much slower landlord expansion of shopping centres and potentially a reduction in existing retail stock with some centres or parts thereof being repositioned or redeveloped into mixed or other uses. This is already starting to play out with Dexus acquiring a Homemaker Centre in Blacktown in Sydney’s south west for possible long-term conversion to industrial space.

Technology will pervade almost all aspects of the more sophisticated retailers’ leasing decision process, from site selection to accurate predictions of rent and sales forecasts, as well as customer tracking. Decisions will be driven by big data from instore cameras, omni channel purchasing behaviours, credit card and banking data and supply chain modelling – all designed to optimise the retail delivery.

On the landlord side, technology will become ubiquitous with unprecedented retailer and customer behaviour data tracking and analysis. Omni-channel retail will become part of the shopping centre experience with physical and digital retail merging in the context of localised needs. This will become the landlords’ point of difference.

There will be more of a partnership and potentially risk sharing collaborations between landlords and tenants. This may include more flexible leasing terms, which allow greater or shorter terms, with opportunities to break leases, upside and downside risk capping on rents and even landlord shared-ownership of tenancies. A good example of this is HomeCo – a JV of several retailers and landlords. As a result, rents will rise and fall much more closely correlated to retailer sales growth which will likely trigger more constant re-basing of rents on reversion to market. The spread in shopping centre cap rates is likely to broaden across retail shopping centre categories, as stabilisation occurs and an equilibrium between demand and supply is reached across locations.

The shopping centre market will likely trifurcate, into three broad categories. The first is centres serving the luxury and premium end of the market, which is relatively immune from the vagaries of the broader retail malaise and price inelastic. The next category is centres with exceptional performance in terms of MAT and pedestrian growth aided by technological innovation and providing customer experiences curated to meet the needs of local markets. The last category represents the undifferentiated centres that serve the middle-and lower-income market offering relatively homogeneous retail mixes. It is this last category where the biggest correction will likely occur.