It wasn’t long ago that to determine the extent of your centre’s trade area, you studied a thick street directory and held shopper surveys over a period of a couple of weeks. You asked shoppers where they lived and then stuck pins into blown-up maps! Today, with location intelligence tools, it’s a different world, and it’s getting more different every day!

We all know that we live in a digital world from which there is no turning back, and I’m here to tell you that in this digital world, location is everything. I am not exaggerating – let me explain.

Reportedly, the first recorded example of location intelligence utilised to solve a significant problem is attributed to John Snow – though not the ferocious fast bowler of the 1970s nor the guy from Game of Thrones. This John Snow was an English physician and, so relevant today, one of the founders of modern epidemiology. Snow was able to identify the cause and then control an outbreak of cholera in London in 1854 by mapping the area where cases were observed overlapped by a map of specific water pumps, having previously theorised that it was the presence of sewage in drinking water that caused cholera. In the nineteenth century, prior to Snow’s groundbreaking work, it was believed that cholera was transmitted and spread by ‘bad air’ or ‘bad smells’ such as from rotting organic matter. This thinking dominated official medical and government positions on the disease, and even the General Board of Health believed in the theory.

No doubt it would have taken John Snow many hours of painstaking work to undertake the necessary research. In fact, a report on his efforts reads thus:

Dr Snow worked around the clock to track down information from the hospital and public records on when the outbreak began and whether the victims drank water from the Broad Street pump. Snow suspected that those who lived or worked near the pump were the most likely to use the pump and thus, contract cholera. His pioneering medical research paid off. By using a geographical grid to chart deaths from the outbreak and investigating each case to determine access to the pump water, Snow developed what he considered positive proof that the pump was the source of the epidemic.

By using what we would today somewhat grandly label ‘location intelligence’, Snow showed that it was all about the location of the Broad Street pump.

So what is location intelligence?

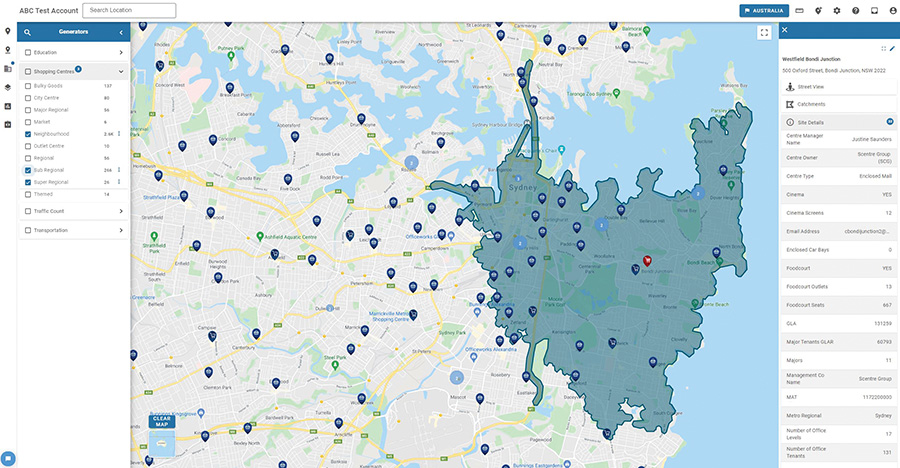

Essentially it is the use of mapping and geospatial data, ideally in combination with a company’s internal customer data, to improve the business outcomes, whether they be related to customer experience or business processes.

Location intelligence companies offer tools that enable businesses to collect and compile big data and then analyse it, filter it and visualise the results, either at a broad or granular level. A picture is indeed worth a thousand words, let alone a series of convoluted Excel tables.

Location intelligence tools also enable decision-makers to visualise spatial data intuitively, which can help uncover trends and business opportunities that traditional analytics tools, without the ‘mapping’ capabilities, miss.

When I started work in the field of economic analysis and advisory for the retail sector and in particular shopping centres, way back in 1982, I understood broadly that location was important, especially for a shopping centre or retailer. Still, all I had at my disposal to examine or analyse the importance of location was Melways or Sydways (hardcopy street directories), plus my own eyes to visit and physically inspect the various locations in which I was interested.

I then had to convey the importance of location, somehow, on the written page. That was usually done by commissioning specific hardcopy maps from a skilled draftsman or trainee architect who would usually take a week or so to prepare them, me having first taken several hours to compile all the information that I wanted to be shown on the map and put together a rough draft on a photocopy – and that was for one task. Can you imagine or, for more mature readers, remember, working like that? Although, even if you don’t go back that far, I would think that most readers will have recollections of large wall maps with coloured pins on them being widely used as tools of the trade.

Fast forward to today – admittedly, in my case, four decades – and consider the tools at our disposal to enable us to quickly, efficiently and accurately examine the role and relevance of location. To help us do so, we have the benefit of GIS (Geographic Information System) which is readily available to anyone – who hasn’t used Google Maps, especially during the past two pandemic dominated years? How critical has location been to each of us over this period, whether it has been our own home address relative to outbreaks, lockdowns, travel restrictions, etc or the locations of our loved ones whom we haven’t been able to see for months at a time because of those same factors?

For the medical authorities trying so desperately to control the disease the question of location – of hotspots, exposure sites, contacts, places visited by each infected person etc – has been even more critical.

But Google Maps is just the entry point. We can access much more specialised GIS services from any one of the dozens, probably hundreds, of available suppliers, each with their own specific datasets and point of interest (POI) data, whether we are interested in the locations of quick-service restaurants, childcare facilities, aged care facilities, supermarkets, gymnasiums, schools, large or small shopping centres, homemaker stores, or all the above. Sitting at our desks we can, with the right tools, analyse the importance of location from any or all perspectives – do I trade better or worse when competitor X is located adjacent to my store or nearby? How important is proximity to a school for my business? Where are the most successful of my competitors situated and what do those locations have in common? What are the characteristics of my best customers, and where can I find more of them?

Similar to our use of the smartphone, location intelligence is now so ubiquitous and accessible that those of us involved in its business don’t give it a second thought. That smartphone is itself now a key enabler of location intelligence available to businesses via mobile device data tracking. Any destination regularly visited by significant numbers of people (eg. any shopping centre) can now, legally, harness the personal mobility data of those who visit to understand where they live, where they came from, how long they stayed, where they went afterwards and so on.

Intelligence on customers’ locations and their movements is now the new frontier in the business of location intelligence, thanks to the smartphone.

Arguably there are few businesses more dependent on location intelligence than shopping centres, though we have all learnt that the business of pandemic control is clearly one. When we consider a shopping centre (or a retail store), the first thing that matters, of course, is its own location. Then there is the question of locations of competitors. Additionally, there is the question of the location of transport facilities – train stations, tram stops, bus stops, etc – and other generators of potential visitation (nearby schools, universities, work precincts and tourist attractions). Then there is the question of locations of impediments to visitation, such as train lines, waterways, etc. With the technology and data available to us today, we are able to consider all of those factors on the same page at the same time, virtually at the click of a button – pun not intended.

Mobile device data from smartphone tracking is the new frontier in granular location intelligence on customers and their behaviours

Of greatest importance to shopping centres is a detailed understanding of the locations of customers and noncustomers, or potential customers, ie. those who could or should be using the store or centre, but for some reason(s) are not doing so. It was not that many years ago that the only method available to explore customer origins and behaviours was a survey undertaken on the premises. Such surveys were annoying for customers, most of whom refused to participate, as well as being cumbersome, time-consuming and very expensive. And visualising the results? Well, that required purchasing a wall map and many hours of work to physically identify each address on that map by placing a red dot on it.

Therefore, such surveys were only undertaken when absolutely necessary, typically years apart. When undertaken, the interview period was usually about two weeks, meaning that a relatively small sample (a few hundred or perhaps up to 1,000) of customers were interviewed. The results from those surveys were nonetheless helpful, and quite statistically sound in most respects once the sample size increased beyond a few hundred.

The emergence of credit card data about a decade ago enabled much more detailed and granular exercises to be undertaken by matching the origin of the credit card bill with the destination of the expenditure. Such data is an example of granular location intelligence being able to offer powerful insights and requiring no surveys. It was, however, and remains today, time-consuming and very expensive.

As I have stated above, mobile device data obtained from smartphone tracking is the new frontier in granular location intelligence on customers and their behaviours. Although such data has now been around for some seven to eight years, and there are several global providers, it is still, in my view, a work in progress. However, while the data obtained is not yet perfect, it is likely to continue to improve in leaps and bounds. The use of mobile device data offers much for the shopping centre analyst, and its particular virtues are that it is cost-effective, virtually instantly available and offers an enormous sample size. Coupled with effective cleaning, analysis and visualisation (mapping), such data can provide great insight effectively on a real-time basis.

Google is, of course, a key player in the business of location intelligence and has much invested in the growth of the sector. In 2020, Google commissioned Boston Consulting Group to prepare a whitepaper based on in-depth research with industry operators titled ‘Unlocking Value with Location Intelligence’. The whitepaper summarises findings from interviews and surveys with more than 500 executives in financial services, retail, logistics and delivery, real estate and travel, to reveal how geospatial data is changing how they do business.

Of the executives surveyed, 95% said that mapping and geospatial data are essential in achieving their desired business results today, and 91% said that they would be even more essential in three to five years. Retail and e-commerce were two sectors where the research found that companies use geospatial data extensively to enhance the customer experience.

However, like any data set, location data on its own is still just data. Furthermore, because of the quantity of data now involved, particularly from customer mobile device usage, we can run the risk of drowning in the stuff or, at the very least, being overwhelmed by the sheer volume.

It is also the case, as is true for all data, that no one customer dataset will ever be perfect. Unless and until we get to the point where every customer’s data is collected, cleaned, analysed and made available to us – the point which I do not believe will ever be reached – then we have to make do with samples. It is the effective analysis of such data, including cleaning and filtering it for possible errors, biases etc, that makes it potentially valuable. And that is also where mapping and visualisation of the data become critical.

A credit card dataset from one bank, for example, might cover a sample of 10% of all transactions. Mobile device data might cover a similar sample. These sample sizes are nonetheless enormous – in the tens of thousands – particularly as compared with the few hundred observations previously obtained by the cumbersome method of customer surveys.

If location intelligence for the retail sector was fundamental before the arrival of COVID, it has become even more critical since.

One unintended consequence of the global pandemic has been a forced restructuring of the retail sector in many ways and much of it for the better.

Initially, COVID threatened to destroy the supply chain and render retailing impotent – how could shops sell anything if customers were not allowed, or inclined, to visit them? But COVID forced retailers to rethink their operations and accelerate the seamless integration of their physical and digital presences. Increasingly, retail businesses are becoming experts in this pursuit, and tracking the millions of individuals’ shopping and transactional behaviours is key to building such expertise. One common finding from those retailers achieving success is that the physical store goes hand-in-hand with the digital presence in optimising the total customer experience. The two channels used together, coupled with that understanding of customer needs, can deliver more goods to more customers in the most cost-efficient manner.

But the challenges and shortcomings of any dataset, which are rapidly increasing in complexity as the volumes of data become so much greater, necessitate careful consideration of the strategy that any shopping centre or retailer adopts in seeking to implement best practice location intelligence techniques to grow its business.

In my view, and concurring with the conclusions of the Google white paper on this point, the focus should be on long-term capability and reliability, ie. developing partnerships with companies that have strong reputations as well as a clear demonstration of technological mastery and, most importantly, genuine expertise in deploying location intelligence platforms and solutions from a retail perspective.