Regarding bricks-and-mortar/online sales, will Australia follow the rest of the world, or will it lead? According to Tony Dimasi, Australia’s online sales are far less than in other western, developed countries. But he also points out that our retail scene – its convenience and sophistication (especially supermarket) – is significantly superior. This article, published in SCN’s Little Guns edition, is supported (as usual) with sound commercial data.

Australia’s retail sector – or at least bricks-and-mortar retailing – has faced many challenges over recent years, culminating in the particularly difficult years of the COVID-19 pandemic from mid-2020 to 2022.

In my view, the single biggest challenge for shopping centres has been, and for the foreseeable future will continue to be, the ongoing drift to online retailing. This is especially so for the centres at the lower level of the hierarchy, which have historically served as largely functional/convenience shopping destinations.

The online challenge in Australia presents both opportunities and threats, it is not all bad news for retailers or shopping centres. What is indisputable, though, is that successfully meeting the challenge of online retailing has added great complexity to the businesses of both retailers and shopping centres.

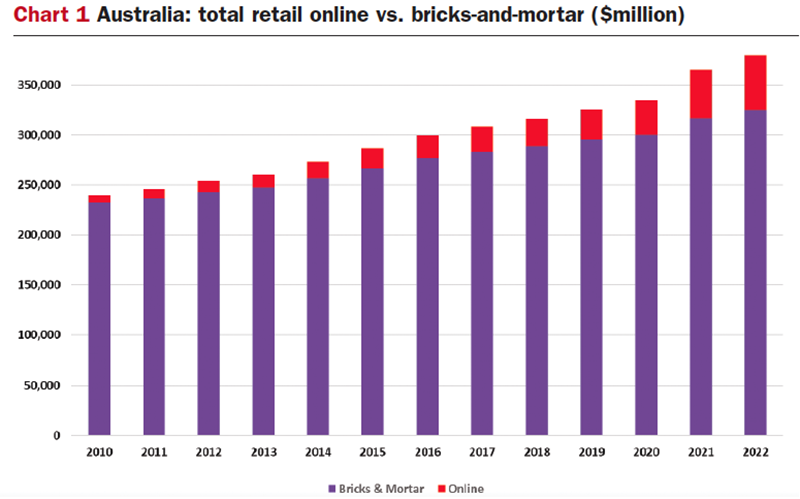

Chart 1

The drift of retail sales to the online channel, both in Australia and globally, was underway well before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as Chart 1 (above) shows, the growth in online market share was generally slow and steady prior to 2020. Across the total retail landscape, the share directed online increased from 3% in 2010 to approximately 9% by 2019, growing by about half a percentage point each year. However, over the next three years, due largely to the COVID-19 pandemic, that share jumped to a now estimated 14.5%.

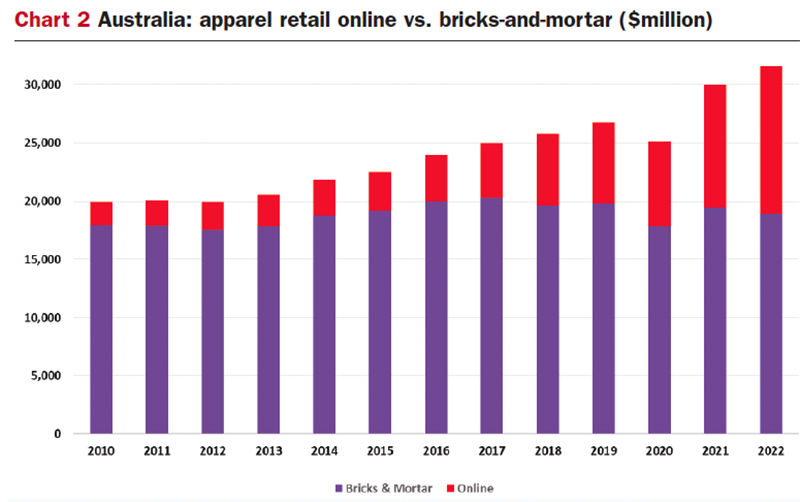

One of the categories that has been most impacted by the drift to online purchasing is apparel (clothing, footwear and personal accessories). As Chart 2 (below) shows, the share of apparel spending directed online in Australia has always been significantly higher than the average across the retail industry, and now sits at an estimated 40%.

Chart 2

From the point of view of Little Guns, which are typically sub-regional shopping centres with a discount department store anchor as well as some representation of specialty apparel stores, this steady loss of apparel sales to the online channel has represented a significant challenge.

In-store apparel sales have barely moved over the past decade, while online sales have grown at an estimated 17% per annum. It is important to note though that not all online sales are ‘lost’ to shopping centre apparel retailers. Around half of all apparel online sales are generated by brick-and-mortar retailers with shopfront premises, with the other half going to pureplay online retailers (eg. The Iconic, Amazon etc). Indeed, the online channel, facilitated significantly by the rise of buy now pay later (BNPL) services, helped the apparel category grow steadily in the lead-up to COVID and during COVID was critical to its survival.

Against the challenges facing the apparel sector, Little Guns have always been able to rely on the critical mass of visitation that is generated by their supermarket anchors, typically the single most important component (in terms of both attracting customers and generating sales volumes) of any Little Gun.

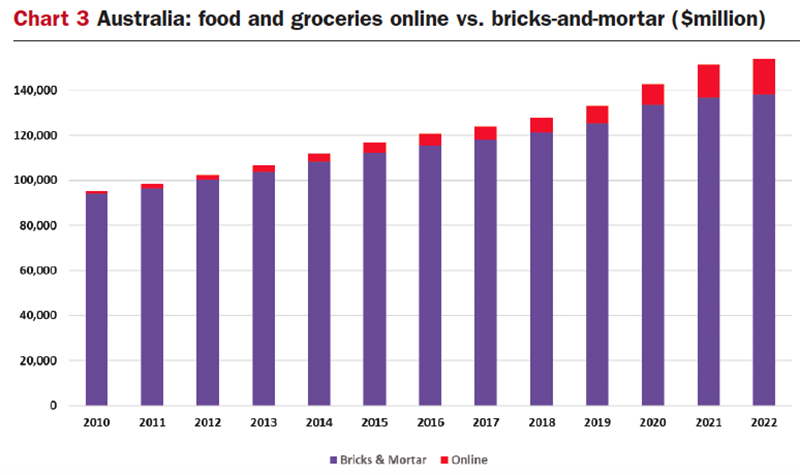

In Australia, the market share of food and grocery spending directed online was remarkably small pre-COVID. The ready availability of supermarkets across all urban areas, their convenient and easily accessible locations, and the widespread practice of purchasing top-up food and grocery items on the way home from work, has generally meant that Australia lags well behind other developed countries, eg. the UK, when it comes to food and groceries purchased online.

Chart 3

The COVID-19 pandemic changed those patterns noticeably, as it changed so many other things. During 2021 and 2022 the share of food and groceries purchased online in Australia almost doubled, from 6.4% to about 11% as shown in Chart 3 (above).

Despite the rapid jump in the share of online sales witnessed during the COVID years, the general health of in-store retail sales has remained robust, for a number of reasons. First, as compared with many other countries, the share of retail sales directed online in Australia still remains relatively modest.

In the UK, for example, the share is approximately twice that which is evident in Australia. Second, even though online sales have grown rapidly and have significantly increased their share of total retail expenditure, there has nonetheless been some steady growth in bricks-and-mortar sales.

Over the past decade, for example, total retail in-store sales have still increased on average by around 3% annually despite online sales growing at close to 18% per annum, while food and grocery in-store sales have also grown by around 3% per annum. In addition, for supermarkets in particular, a substantial proportion of online sales fulfilment occurs via the store network, ie. the orders are filled at the store and then either delivered to the home or, increasingly, collected by the consumer at the supermarket’s Click & Collect point located outside the store.

For all these reasons, in Australia, we have not yet seen the significant negative impacts on in-store sales – other than in the apparel category – that have been evident in many other countries. That is not to say that in-store sales have not been impacted, but the level of disruption to this point has not been such as to dramatically change the store network strategies of many retailers. There remains a considerable appetite for additional physical stores, though hand in hand with a desire to benefit from an even more rapidly growing online channel.

In-store apparel sales have barely moved over the past decade, while online sales have grown at an estimated 17% per annum

For Australian retailers, the impacts of the drift to the online channel have also been softened by the fact that:

a. Typically, more than two-thirds of online purchasing by Australian consumers are directed to Australian retailers (ie. not overseas); and

b. The bulk of online purchasing, about 60%, occurs via the online channels of traditional retailers, which have now become multi-channel. Less than half goes to pureplay retailers.

An interesting case in point, specifically in relation to food and grocery retailing, is Amazon. With its acquisition of a substantial supermarket chain in the US (Whole Foods) in 2017, and the subsequent rollout of its Amazon Fresh stores, the world’s largest online retailer admitted that if it was to have any chance of making progress in the food and grocery market, it needed physical stores. Yet five years later, there appears to be little confidence that Amazon will be able to successfully compete in that market against US giants such as Kroger, Albertsons, Target and Walmart, let alone the various strong regional supermarket brands that operate throughout the US.

Some analysts have recently described Amazon’s food and groceries play as an ‘expensive hobby’. Amazon spent US$13.7 billion to acquire Whole Foods, and despite those efforts, as well as the rollout of its Amazon Fresh stores, it is estimated to account for just 2.4% of the food and grocery market in the US.

As always, when it comes to the topic of online retailing, the most important and most difficult question to answer is when and where will things settle, ie. what can we expect to see in terms of continuing erosion of sales to the online channel and what will it mean for the physical store/shopping centre?

The answer, at least according to most retail operators across the globe, is that there is still a long way to go and that, in broad terms, we are likely to see in the order of 40% – 50% of total retail spending occurring through the online channel over the longer term, ie. by say around 2050. Analyses of the implications of such a continuing transfer from the store to online, in European countries, have concluded that the consequences for the physical store network could amount to losses of more than 50% in-store profitability.

Continuing technological developments in warehousing and fulfilment, as well as delivery logistics, are expected to drive substantial improvements in the profitability of online sales

Whether or not that ends ups being the case remains to be seen, especially since many online retail operations, particularly in food and groceries, are still unprofitable. However, continuing technological developments in warehousing and fulfilment, as well as delivery logistics, are expected to drive substantial improvements in the profitability of online sales. The reality is that at this point, we do not know exactly what those technological changes will end up looking like, with developments being predicted in automated warehousing, dark store fulfilment technologies, electric vehicles, Artificial Intelligence routing, drones and autonomous vehicles and even virtual reality shopping via the metaverse. Some of these ideas might sound a little far-fetched at the moment, but we have learned enough about the continual evolution of technology to appreciate that almost certainly breakthroughs will come.

What we can be reasonably confident of, therefore, is that there will be rapid and ongoing change and that the fulfilment/delivery models will be continually refined until a profitable alternative is found. I think we can also be confident that the proportion of retailing that occurs online will continue to increase and significantly so.

It is also the case, in my view, that different outcomes will eventuate in different countries. Factors which determine the extent of transfer to online retailing across countries include the level of digitalisation, the level of technology, the degree of urbanisation, wage levels, and the availability, ease of use and general attractiveness of the physical store alternative. Supermarket operators in Australia, for example, expect to see significant growth in the share of food and groceries purchased online, but not to the same level as is already being achieved in the UK, let alone the expected future level in the UK.

Ultimately, the future of the physical store will depend on the continual growth in total retail expenditure and the potential for growth in physical store sales despite the rapid growth of the online channel – as has occurred across most categories in Australia over the past decade. It will also depend on the role(s) that the store plays in the logistics and fulfilment processes.

In addition, research undertaken both in Australia (by Quantium) and in the UK (by CACI) has pointed to a significant role that is played by the physical store in optimising online sales, referred to as the ‘halo effect’. The research has concluded that in most cases, the existence of a physical store leads to significantly greater online purchasing by customers who live in the store’s catchment. The research shows that the stores can be powerful tools to connect customers with brands, even leaving aside the actual role which the store might play in the fulfilment process.

Australian consumers are enthusiastic enough users of the online channel but always lagging behind the global leaders. The reasons for this, I think, lie in the physical store networks that are conveniently available, the attractiveness of our shopping centres generally and the social role of physical shopping. The ‘halo effect’ of the physical store is also something which many Australian retailers appreciate and successfully harness in delivering their omnichannel strategies. My view is that in Australia, we will also see substantial further growth in the share of retailing directed online, but that change will continue to be more modest than the global benchmarks.