We see countless examples of old buildings being given a new life as old industrial structures are transformed into modern venues. More often than not, ‘retail’ in new forms – experiential retail – is the solution. It’s happening all over the world.

While the concept of adaptive reuse is certainly not new, in the past decade more cities than ever are hopping on board with the idea, whether because of nostalgia for old times and the desire to preserve historic landmarks, the lack of prime land, or simply to address concerns surrounding land degradation and conservation.

Undoubtedly, the process of adaptive reuse is inherently green since there are few more wasteful practices than tearing down an existing building and replacing it with something entirely new. Hence, this approach has become a popular alternative to demolishing the derelict and disused structures that nowadays coincidentally often sit on prime real estate. These buildings also commonly have a heritage value, and while not all have outstanding architectural or aesthetic credentials, they make up for it through a character that comes from age and use.

By common definition, adaptive reuse is the process of repurposing obsolete, abandoned and underutilised buildings for different uses or functions while at the same time retaining their historic value and features. At its core, the concept is about repurposing an old building into something new. A rundown school may be converted into apartments, a warehouse is turned into a food market or a derelict factory finds a new life as a museum. In some cases, entire industrial neighbourhoods have been reborn into vibrant retail destinations and eating hotspots, such as SoHo and the Meatpacking districts of New York.

Retail businesses, in general, are particularly adept at engaging in adaptive reuse and following are some recent notable projects that show how imagination and intelligent design can deliver striking transformative effects and breathe new life into old buildings.

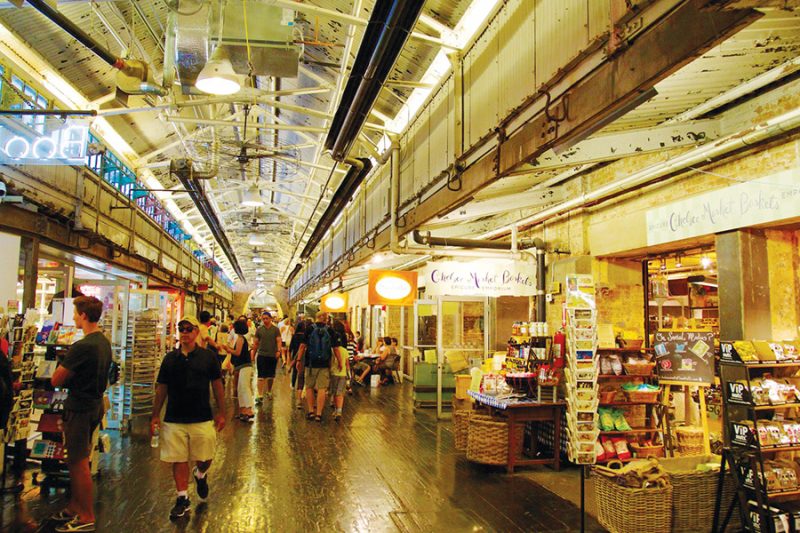

Chelsea Market, New York

Market share

Food halls, craft breweries and distilleries and maker-to-retail concepts are increasingly taking advantage of the continued movement of adaptive reuse. Old factories, warehouses and docks are usually perfect for such uses as they are robustly built and grand in scale, they are unique and rich with architectural character and soul, and they often cost less. Further, reuse of older buildings is a more environmentally sustainable approach than building new, appealing to many modern day retailers and consumers alike.

Early adaptive reuse projects leading the change, such as Chelsea Market in New York and the Ferry Building in San Francisco have quickly become iconic retail and food destinations followed globally by the entire industry. Closer to home, recently completed food hall projects taking on vintage buildings include examples like The Cannery, an innovative redevelopment of the 100-year old Rosella tomato soup cannery in Sydney’s Rosebery. The Cannery brings together the best providores, restaurants, bars, lifestyle brands, artisan food, craft brewery and distillery, commercial spaces, cooking school and regular weekly markets.

The Cannery

Then, there is the widely cited Tramsheds project within the old Rozelle Tram Depot, a European-inspired food hall housing some of the Sydney’s most unique and innovative food offerings alongside a variety of services for the local community, including a supermarket, hairdresser, gym and medical centre.

Over in Europe, working with a relatively similar structure to Tramsheds, Swedish practice Wingårdh has turned a dilapidated 19th-Century freight depot into a bustling award winning food market, setting a precedent for the transformation of Malmö’s industrial docks. The new Malmö Saluhall market hall inhabits the brick shell of a freight warehouse that was left to crumble after the last train departed in the 1950s. The existing building has been thoughtfully renovated with weathered steel cladding and red-rust facades reminiscent of the industrial character that has long dominated the area. The original warehouse is retained as a single, impressive volume with an internal busy market street of different shops, restaurants and street food stalls spread between different seating areas. Outside, a public square next to the Market Hall building doubles as an outdoor dining area, event space and a produce garden.

Malmö Saluhall Market Hall

Like many industrial cities, Malmö is currently in a state of transition, from being a hard-working port that once hosted the largest shipbuilding dock in the world, to a post-industrial urban centre. The Saluhall area itself is positioned right on the city periphery, yet to be immersed by the Malmö’s wave of urbanisation, however, the Market has already become a destination in its own right, bringing people daily to the once solely industrial area, something that probably would not have happened had the building been developed as an office space as initially proposed. In some ways, this new market hall may resemble the trendy food halls often characteristic of urban gentrification that have popped up across the world, but in this overlooked part of Malmö it brings new life, rather than replaces the old.

Responding to changing consumer demands and tastes, microbrews and adaptive reuse became two great urban trends very much tied together and, like markets, craft breweries have been increasingly credited for revitalising once neglected neighbourhoods and helping local economies.

In order to minimise initial costs, get a bigger space and of course deliver on character, craft breweries tend to open in old, crumbling structures located in more edgy or industrial areas. As a result, they now occupy buildings that were once fire stations (Firehouse Brewing Co, Rapid City, US), garbage incinerators (Junction Craft Brewing, Toronto, Canada) or even funeral homes (Brewery Vivant, Grand Rapids, US), to mention just a few.

Firehouse Brewing Co

In Australia, one of the pioneers of this movement, Little Creatures Brewery, has successfully transformed old structures into urban craft breweries for almost two decades, starting from the former crocodile farm in Fremantle to most recently an old wool mill in Geelong.

These have now become ‘institutions’, with not only epic barrel halls and 24-hour working breweries, but also multiple bars, inside/outside dining areas, music venues, a gallery and even a bocce court.

Little Creatures Brewery, Fremantle, WA

Mall reborn

Global retail experiences are changing as architects explore new paths, redefining what a ’mall’ should look like. In process they are increasingly taking advantage of old inner-city real estate for their reinventions. Recently, highly acclaimed British architect Thomas Heatherwick unveiled his version, Coal Drops Yard, London’s newest retail destination and the last slice of Victorian-era King’s Cross to undergo adaptive reuse.

Already considered by many as London’s most successful makeover, Coal Drops Yard brings something entirely different to London’s shopping and dining scene. Heatherwick has transformed the two Victorian coal warehouses into a contemporary retail quarter that celebrates the site’s industrial heritage through a daring architectural gesture while offering a brand new place where art, commerce and culture come together.

This ‘mall’, as senior retail executive Craig White puts it, is “not about consumption – you can get that online. It’s about delighting people.”

The cobbled streets and brick arches topped by the two highly Instagrammable ‘kissing’ roofs are home to a mix of independent retailers and signature brands that host lectures and workshops, not only sell things. Under the arches, the project also provides a new major public space for the city where concerts or performances can be hosted or simply provide a much needed new place for human interaction.

Coal Drops Yard, London

Heatherwick actually wanted to make something that isn’t like a shopping mall at all as his interest is in the social chemistry of the buildings and “shopping is just an excuse for being there”. Hence, as the Coal Drops Yard website reads, this is no piece of faceless architecture catering to mass supply and demand, but part of London’s fascinating industrial and cultural past, full of stories, that’s been sealed-off for years. Today, reimagined, “it allows everyone to experience these rich and characterful buildings and provides the backdrop for something that’s very London, and very much now”.

For something different but equally as impressive, Dutch architecture firm OMA has restored the historic Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venice, adding new entrances and bright red wood-panelled escalators to turn the 16th-Century building into a DFS department store. Located beside the iconic Rialto Bridge, the Fondaco has had many lives since it was first built, it has served as a trading post for German merchants, a customs house under Napoleon, and a post office under Mussolini. It was granted legal monument status, which meant that OMA’s interventions had to be strategic and minimal. A new rooftop terrace was added and the structure opens the courtyard piazza to pedestrians, maintaining its historical role of covered urban ‘campo’. Some aspects of the building, lost for centuries, have even been resurrected with the walls of the gallerias once again becoming a surface for frescoes, reappearing in contemporary form.

Fondaco dei Tedeschi, Venice

The Fondaco dei Tedeschi is now a major retail destination and vantage point for tourists and Venetians alike, a contemporary urban department store staging a diverse range of activities, from shopping to cultural events, social gatherings and everyday life. OMA’s renovation, both subtle and ambitious, continues the Fondaco’s tradition of vitality and adaptation, its preservation yet another chapter of the building’s illustrious and multifaceted history.

What’s old is new again

Due to their size and character, probably the most popular practice has been turning old rundown structures into arts, entertainment or mixed use venues, think the Tate Modern! One of the more recent successful examples is Shanghai’s Shipyard 1862, an old shipyard on the Huangpu River that Japanese architect Kengo Kuma has transformed into a vibrant mixed-use space housing a theatre, boutique shops, restaurants, galleries, luxury car showroom, commercial spaces and multi-purpose halls. The refurbishment took more than five years to complete in order to preserve as much of the original texture and materiality.

Original brickwork was restored wherever possible but for the rest Kuma designed a pixelated ‘hanging brick wall’, a signature feature that successfully blends old with new.

Kengo Kuma has transformed the Shanghai Shipyard

In Maastricht, Holland, after extensive restoration the former electric power station and boiler houses have been transformed into the new art cinema Lumière. The complex consists of the listed machine hall, two boiler houses and a carpentry workshop that links the machine hall to the other buildings in the culture cluster. In the boiler houses are six new cinemas, with a total capacity of 500 seats, stacked according to the box-within-a-box principle while the beautifully decorated listed machine hall now provides space for a popular restaurant and bar. The complex is part of the new urban development project on the inland harbour, within which the culture cluster will serve as a boost for the future redevelopment of this former industrial area.

Lumière Cinema Maastricht

Evidently, retail led adaptive reuse allows us to take a second look at old structures and it can empower cities to make more effective use of space for people and businesses. In short, rather than building more, we should strive to build better.

Moreover, we need that diversity of buildings within the built environment because that adds to a city’s charm and attractiveness and makes it more liveable. And even though modern buildings can sometimes be attractive solutions for disused sites, they could potentially remove any legacy and connection with the surroundings, but with adaptive reuse strategy we can in fact maintain urban cohesiveness and continuity, reduce urban sprawl and help preserve the historic character of cities while still moving them towards the future.