Cap rates used to move in predictable ways. There was always a constant and definable relationship between Cap rates and Bond rates. Not anymore. Today, it’s like someone’s kicked the table over; cap rates are all over the place. But that could present some great opportunities…

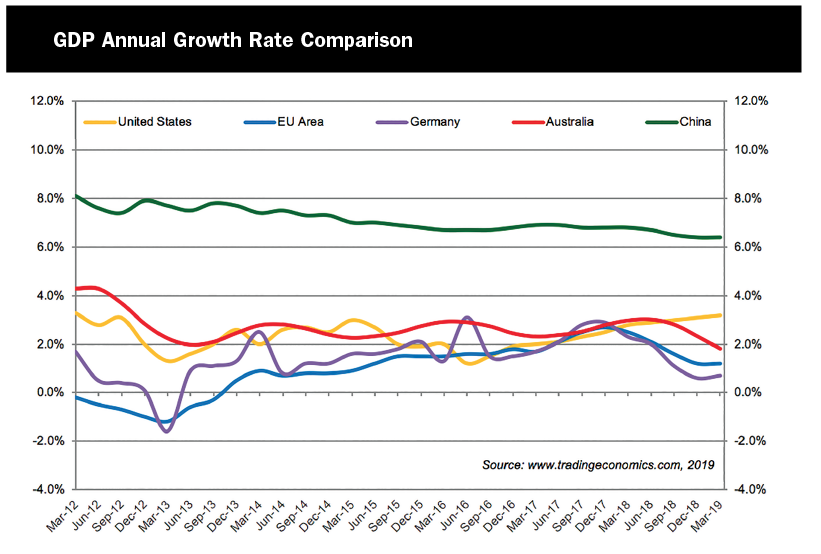

Australia has entered a period of softening conditions. We aren’t alone though, which is nice – misery does love company.

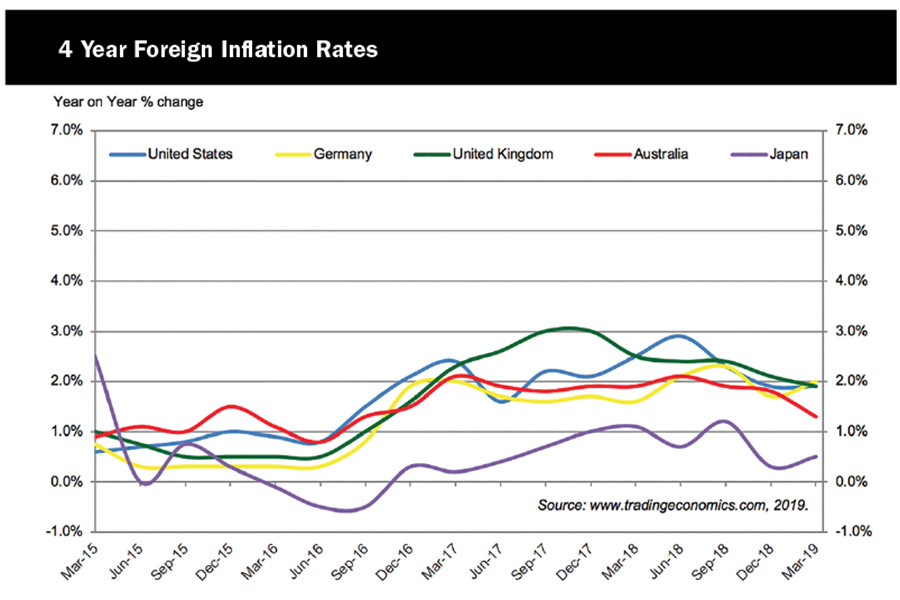

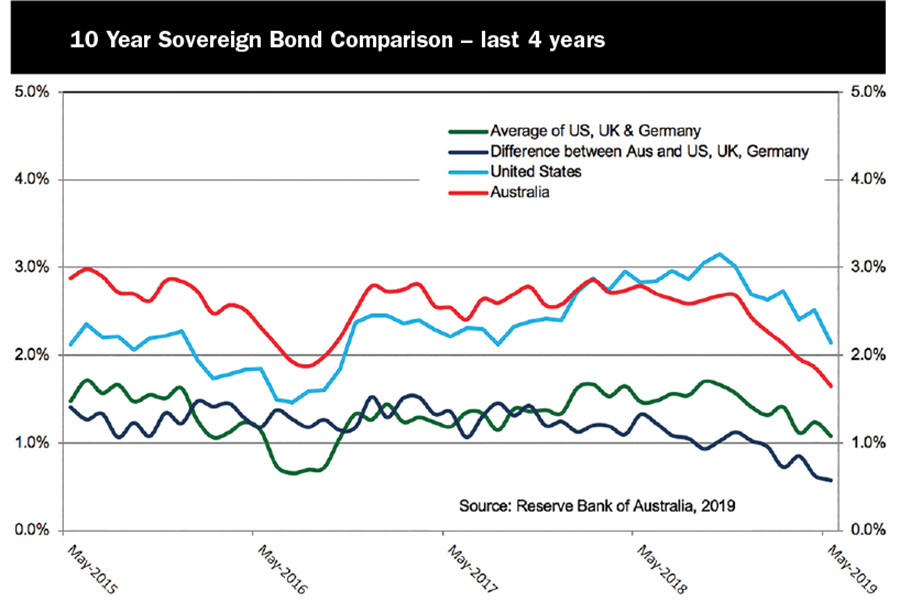

This is also being played out in globally falling inflation rates – which in turn is being reflected in globally falling bond yields – a reversal of a rising trend 18 months ago.

The rising stock market against this background is confounding enough. Even more confounding is the turning of the old order on its head. Industrial returns are in some markets exceeding CBD office and retail returns in that order. Industrial and exciting aren’t usually in the same sentence!

But we should be used to this by now – the new order is that the old order doesn’t count anymore.

That being said, all old property heads regard capital growth solely via yield compression as folly and that has not changed. Yes failing cash yields should mean cap rate compression, but deflation can be a medium term income trap – and compressing cap rates don’t often outrun rents caught in a deflation cycle. This is not all property, just some – just all the property whose highest and best use is about to change.

The paradox here now is cap rates vs income. Shall we look outside the property boundary perhaps?

Over indebted nations and falling inflation sounds a lot like Japan since 1989. In Victoria alone, CPI was reported in March 2019 at 1.2% – and at a time of one of the greatest infrastructure spends in our history, nearly full employment plus population growth of about 100,000 people a year. These things do not usually add up to a falling inflation rate and all our governments are becoming more indebted. Looking more broadly, this appears to be a global deflationary era slowly evolving before our eyes.

That being said, property rents are not solely related to inflation in the economy – in fact far from if it one looks at CBD office rental rates in Melbourne and Sydney. Property rents broadly though are very related to population growth and supply.

Retail income growth – roughly – is the sum of population growth + wages growth + inflation minus competition minus capex.

Population growth with no competition is the light on the hill of retail investment – particularly now with no wages growth or inflation – assuming you’ve priced in all your capex – you did listen to me on that point last year, I hope?

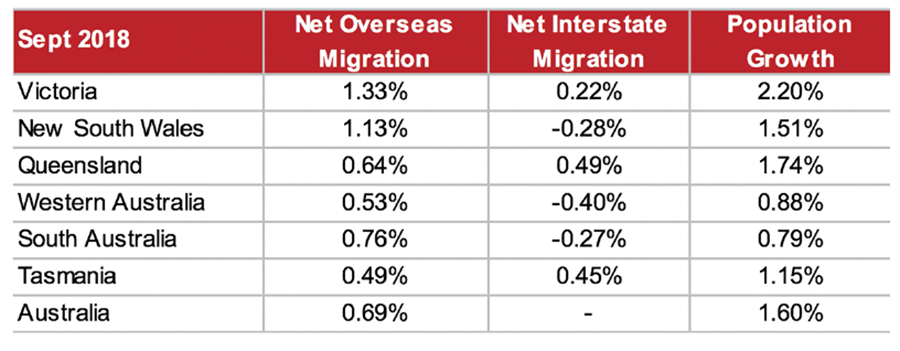

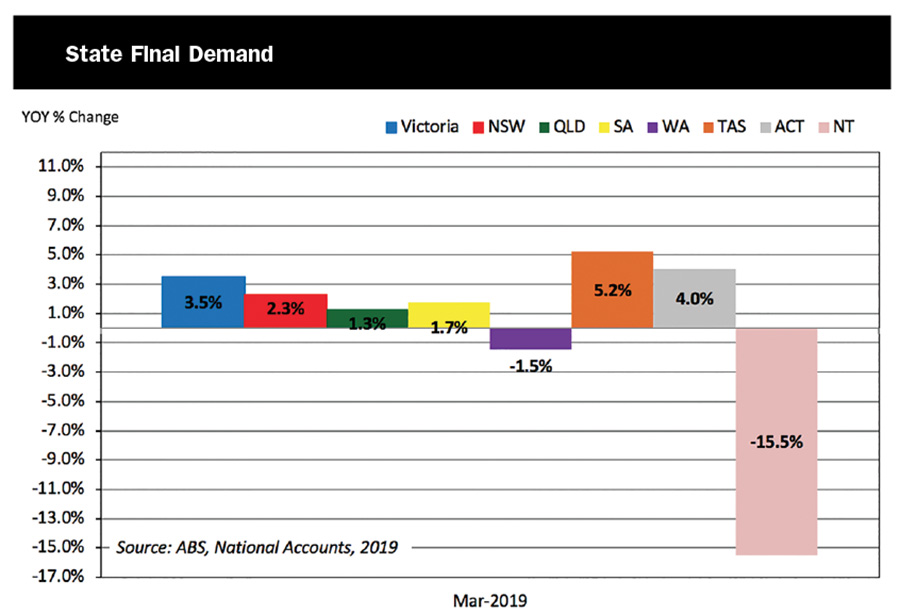

Right now people are doing what they have always done – and particularly since gold was discovered – they move to opportunity. The population growth variations across states are stark. It’s a sort of chicken and egg circle that has much to do with the economic growth of individual states to date and its outlook going forward.

Both Victoria and NSW remain the powerhouse states enjoying historic highs in population growth – and this will infer greater separation in the property outlook (and prime property yields) between states as this trend becomes more entrenched. Note though, it’s all about overseas migration. If overseas migration were to change, a lot of other things will change too.

In terms of supply, online is now the modern department store and this is a two edged sword.

Yes it means competition you can’t touch, but it also means there are no longer the anchors to support a new subregional centre; nor the expansion of a convenience or subregional centre to a larger scale (except on a few rare occasions). That’s a very important point as we look forward. A regional or subregional centre with the benefit of population growth in its catchment – and there aren’t many of them – isn’t likely to get new competiton from this population growth in the foreseeable future because of the anchor decline.

So the new order has its benefits – population growth and competition constraint are benefits we haven’t had before. However, take these out and the spending outlook in some centres will be a challenge.

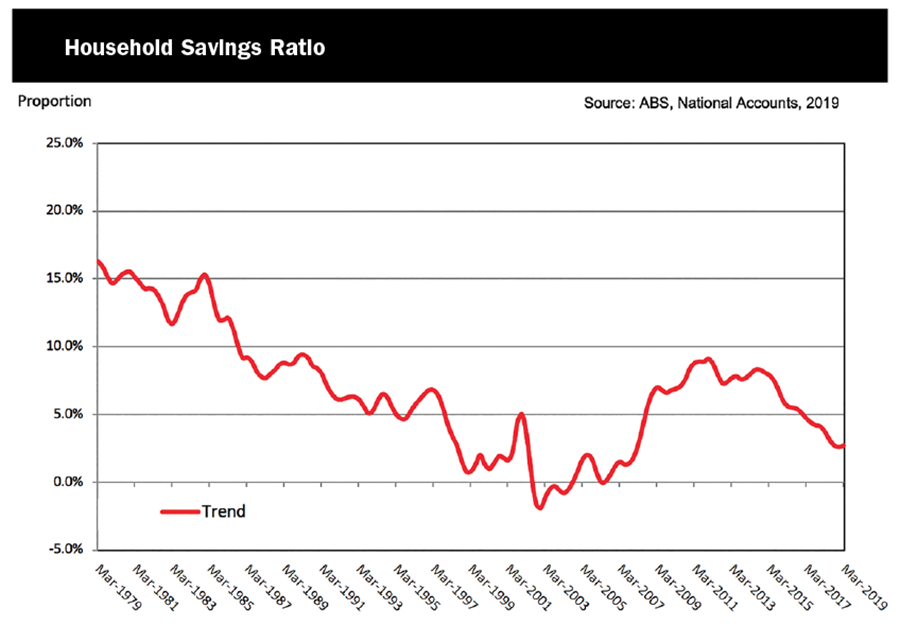

We all know the wages growth story. It’s persistence, since the GFC really, which tells us is that there is significant under employment across the economy – more kindly put as ‘capacity’. Strangely though we all feel we are working harder than ever! What is really interesting is household savings. Falling household savings historically occasions improved spending – because rising wages and house price growth super charge consumer appetites and people spend more than they earn (even me).

The difficult times in retail since the GFC could be blamed on household austerity until about 2012. Since 2012, falling household savings and a rising housing market should have turned on retail spending. Not so this time however.

The housing market is teaching all sorts of hard lessons, but the affect of no wage growth against rising living costs – and transitioning to principle and interest payments – is clear. I don’t think anyone really believes that reducing interest rates from low to really low will change the problem we have with discretionary incomes.

This problem however is most centrally a retailer’s problem. For retail property investment – which is fixed in one place on the ground and not tied in perpetuity to a single going concern, it’s not just about discretionary income but offer and scale – as scale offers versatility.

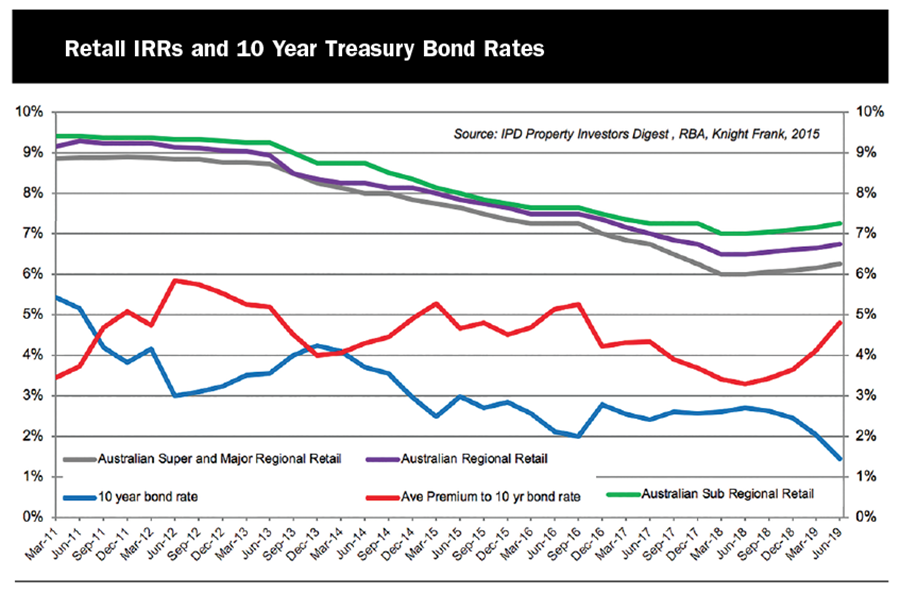

And so to cap rates. The cap rate is the outcome of the total return demand less growth – or alternatively – cap rate plus net growth = IRR.

It is the market’s total return expectation that governs ultimately where cap rates go – provided growth is static – and this is precisely the point.

It’s not a given that retail centre cap rates are going to contract across the board in this cycle.

Right now, property looks very cheap on traditional measures against bonds, but that is only if growth is not challenged. Bonds are low now because growth is challenged.

History has shown property cap rates don’t contract automatically with bonds, and only contract when the following two factors are in place:

- Economic stability remains in place

- The market concludes the falling bond trends has an element of permanence rather than bond volatility.

While the US bonds are trending down, Australian bonds are now lower than US bonds, which rarely lasts more than a few months.

Right now, it’s very likely that cap rates for convenience centres and long let supermarkets may contract quite quickly this year but this isn’t related to the growth outlook but a combination of a retiree/self-managed super funds (SMSF) flight from cash and negative residential sentiment. It’s classic reallocation of uniformed capital.

Syndicators could experience a boom and falling borrowing rates means improving arbitrage. This will be painful when the cost of capital does rise – because most of these assets are stuck with long dated leases with no rental growth – but who can see that happening anytime soon – and if you are 70 or 75, will it matter then?

For the larger subregionals and regional centres there is no broad brush statement that can be made about the sector because of the enormous variation in catchment and competition hierarchy fundamentals so unique to every centre.

Generally speaking, sentiment has softened – most certainly for non metropolitan subregionals for obvious reasons – however, there are no sales in the super prime area and very few regional centre transactions to point to benchmark this sentiment against.

The fortress trophy malls, which almost never come to market – particularly those that have had the rents marked to market already – are considered to have been the more resilient and this is being tested at present with a number of offerings brought about by structural capital reallocation.

What this scenario does mean, is that cap rates across markets and property types that have previously moved in unison will now diverge following traditional valuation fundamentals – and primarily the growth outlook – and sets the stage for shopping centre yields in particular to move in different directions (up and down) according to the growth outlook peculiar to each centre.

It’s going to be very messy. The trick will be not to be caught missing the income picture against an enticing arbitrage; and choices on realising now or in the future. The market is in a transitory stage whilst it digests the changing economic outlook against the falling cost of capital – and looking back, it is often at this point that prime assets – like assets with population growth and/or limited competition threats – can become good buying in cyclical terms.