Francis Loughran looks at F&B in Mini Gun centres. He finds that overall they could do better and so increase income, achieve a higher asset value and improve customer satisfaction.

The most successful shopping malls around the world are transitioning into living centres, complete with dining precincts, and retail and entertainment collectives. In order to maintain their place in the competitive hierarchy it is crucial that Mini Guns and shopping centres of all sizes, continue to evolve.

In this regard, food and beverage (F&B) continues to lead the way, yet most Mini Guns have yet to attain their maximum potential in both GLA and MAT terms.

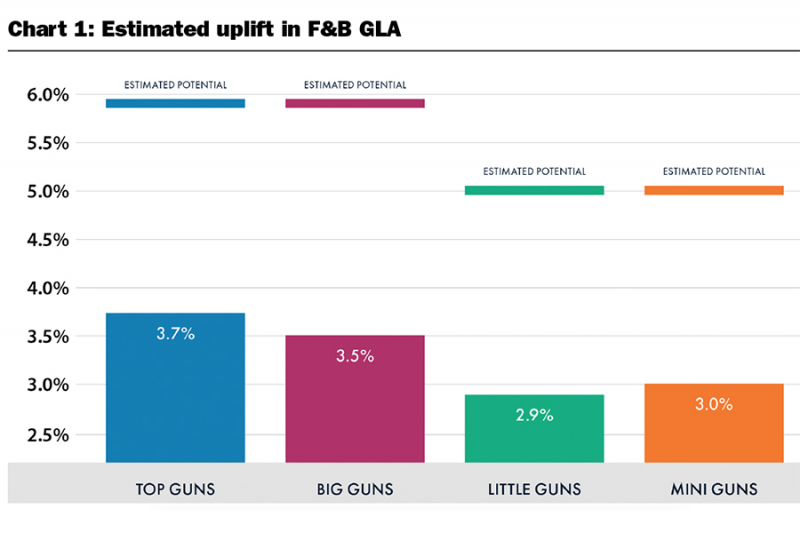

Our research on Mini Guns shows that these centres could support about 5% of their GLA being devoted to food and hospitality.

In general, F&B in Mini Guns takes up between 2% and 4% of total GLA, so there is considerable room to expand the offer. Chart 1 (above) shows our estimates of the average proportion of F&B and our estimate of the Base Case for F&B as a percentage of total GLA.

While we recognise that many people have a gut feel that there is already “too much food”, the market is much bigger than those people realise.

According to ABS data, the total market size for prepared food and hospitality is approximately $77 billion – or about $3,000 for every man, woman and child in Australia. Most shopping centre owners, developers and landlords have been failing to identify the importance of the ‘business of food’ as a retail category and take their fair share of the pie.

Furthermore, today’s informed customers are no longer prepared to accept over-priced average food, poor service, bland dining environments and predictable food mixes from either their neighbourhood or super-regional shopping centre. Building critical mass for your food through evidence-based food optimisation business modelling aims to secure responsible sustainable volumes of food and hospitality aligned with each centre’s size category, whether they be Regional, Sub Regional or Mini Guns.

The optimisation of food and hospitality relates as much to optimising the volume of food and hospitality as it does to controlling the oversupply of food.

Chadstone food court

More importantly, additional F&B creates a real and sustainable point of difference and new customer markets – both through its own demand but also with its proven flow-on effect on dwell time and increased spend to non-food store and entertainment – therefore maximising market share.

Still, Mini Gun landlords would be right to question whether this is the time to increase GLA for a non-discretionary category. In the RBA’s minutes from its July 2019 meeting, where it lowered the official interest rate to just 1%, the bank highlighted that consumption growth had “remained subdued” and that spending on discretionary items “had fallen in the March quarter” and that retail trade figures showed that discretionary spending “had remained soft in the June quarter”.

The short answer is: Yes, it is a good time to consider increasing the GLA devoted to F&B. Moreover, the competitive environment in which Mini Guns find themselves means that creating a sustainable point of difference is more important than ever.

Let’s look at the numbers first. After analysing the latest retail trade data from the ABS, we have found the following:

1. In the last year for Australia as a whole, F&B retailers saw their sales grow faster than the retail industry as a whole. Breaking this down by state, as shown in Chart 2 (above), only Queensland, South Australia and the Northern Territory saw F&B grow slower than the overall state retail industry.

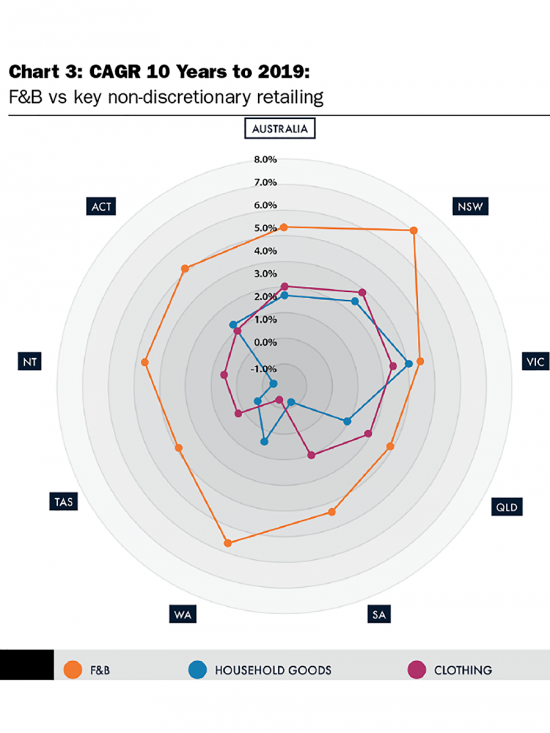

2. Furthermore, this trend is a continuation of the growth that has taken place during the past decade. Chart 3 shows that for the past 10 years, in every state and territory, spending at F&B retailers has not only outpaced that of retail trade as a whole, but also the key discretionary retailers in household goods and clothing and footwear.

Subject of course to the demand profile of each centre’s catchment, the overall message from Australians across the country is that they value the experience and the fun that quality food and hospitality operations bring to their lives. Furthermore, they continue to desire this type of retailer over and above Department Store Type Merchandise (DSTM) specialties.

Because Mini Guns are geared more towards convenience, landlords have generally concentrated their leasing on convenience-oriented F&B outlets. This leads to a homogeneity of offers and reinforces the stereotypes, or ‘class structure’ if you will, that Mini Guns are poorer cousins in the social strata to Little Guns and Big Guns.

While Mini Guns have a smaller offer, it should not be an inferior offer to what can be found in the larger centres.

This is especially true as Mini Guns are subject to much more competition than Big Guns. It is not unusual for a Mini Gun to have half a dozen competitors (strip centres, stand-alone supermarkets, bulky goods centres, other Mini Guns) within a five kilometre radius. As such, it is important for a Mini Gun to do whatever it can to stand out in this crowded field.

A well thought out F&B offer, attuned to local demand and gaps in the market, can deliver a competitive edge to a Mini Gun by providing the type of hospitality that customers have come to expect when going into a regional shopping centre.

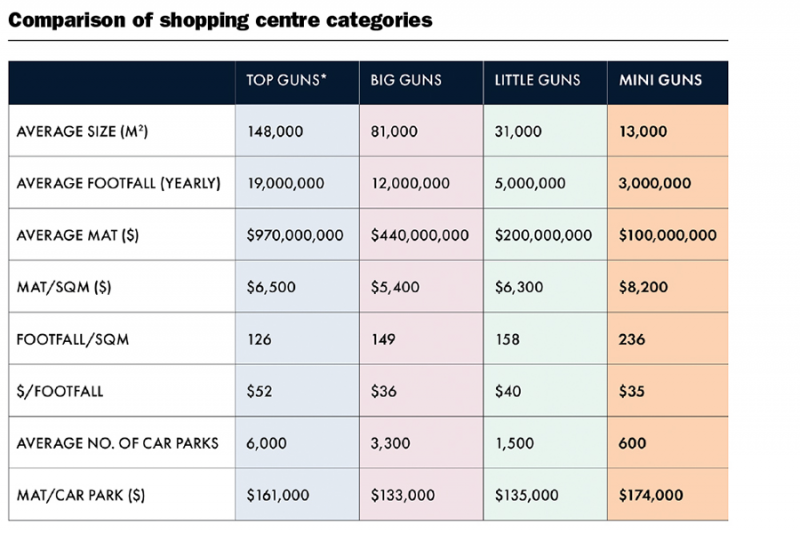

Furthermore, the possibilities for a successful F&B precinct in a Mini Gun are strong because the intensity of use at a Mini Gun is much greater than that for a Big Gun.

Normalising the comparison between centre types shows that larger centres average a footfall of 126 people per square metre of GLA, while for Mini Guns the benchmark is 236. In looking at MAT per car park, Mini Guns also outperform the larger centres, $174,000 of sales/car park to $133,000 for Big Guns.

Two brief case studies can illustrate the opportunities. The first involves a larger Mini Gun in a medium-sized regional city that is the largest, and only, managed shopping centre in the area. All of the city is within a 10 minute drive of the Mini Gun, as are all of the stand-alone supermarkets, discount department stores, mini-majors and bulky goods retailers. Currently, there are 10 F&B outlets accounting for about 600m2, or about 3% of GLA. Given the demand in the region, this centre could increase its F&B offer to 1,000m2. Additionally, this new GLA could be used to bring more experiential retailers into the centre, as the current offer is a mix of QSR (eg. donut, kebab, sandwich, juice) and a couple of national fast food chains.

The second Mini Gun that we’ll look at is in western Sydney and has other shopping centres and a significant amount of other retail all within a 10-minute drive. This centre has nine F&B outlets with more than 500m2 of GLA made up of relatively small floorplate QSR outlets and this centre too could support another 400m2 of F&B. Even though the centre is busy and healthy, this is not a food and hospitality mix that makes this centre stand out. Creating a mix that has the breadth and scope of those in Big/Little Guns would create a sustainable point of difference for the centre and would lead to increased asset value.

Time and time again, the value of strategically quantifying the sustainable volume of food and hospitality has been proven to have tremendous return on investment. In so doing, landlords should find that overall revenue and dwell time increases.