In the first of a two-part article, Susanne Pini explores the effects new trends in the consumption of food and beverage have on retail outlets, the retail scene in general and therefore on our centres. She looks at the ‘Time Out Market’, launched in Lisbon in 2014.

Whether it is caused by the global democratisation of food culture and the effect of the popular cooking shows or it’s a product of the economic times and the ‘Amazonification’ of the food industry, it’s clear the general public now expects access to high quality food everywhere: at home, in shops and restaurants. In fact, many of us won’t settle for less, or as IBISWorld’s Robert Bryant puts it, “the country’s new foodies seek out top-class tucker”.

The MasterChef Effect

Love them or hate them, it cannot be denied that the ratings juggernauts like MasterChef and My Kitchen Rules have had a notable impact on our eating, cooking and shopping habits. They have encouraged us to try new ingredients and new techniques, buy new kitchen gadgets and to discover new chefs and restaurants. They have changed the way we view food and helped the food movement shift from the traditional meat and three veggies to the fine dining revolution.

MasterChef, one of the most influential food programs globally, has even inspired its own term – the MasterChef Effect. This term was coined early in the life of the show and refers to the effect on the cuisine and produce the show has inspired. Techniques such as sous vide, tempering chocolate or making ballotines have entered the culinary repertoire of our kitchens, thanks to the MasterChef Effect. Even the term ‘plating up’ is now in the popular vocabulary as a result of the show.

With such an intense focus on fine food and the unique ingredients used to create it, the general public has developed a taste for gourmet foods that were once exclusively targeted at affluent consumers who had the knowledge and the means. Coles, a major MasterChef sponsor has reported a 1,400% spike in the sales of what it terms ‘unusual’ or gourmet ingredients, after they feature in the show. The list goes on. MasterChef is having a huge impact on the nation’s food industry as a whole, according to IBISWorld research.

Cooking schools, kitchenware retailers and top-end restaurants whose chefs are invited on the show have all been cashing in.

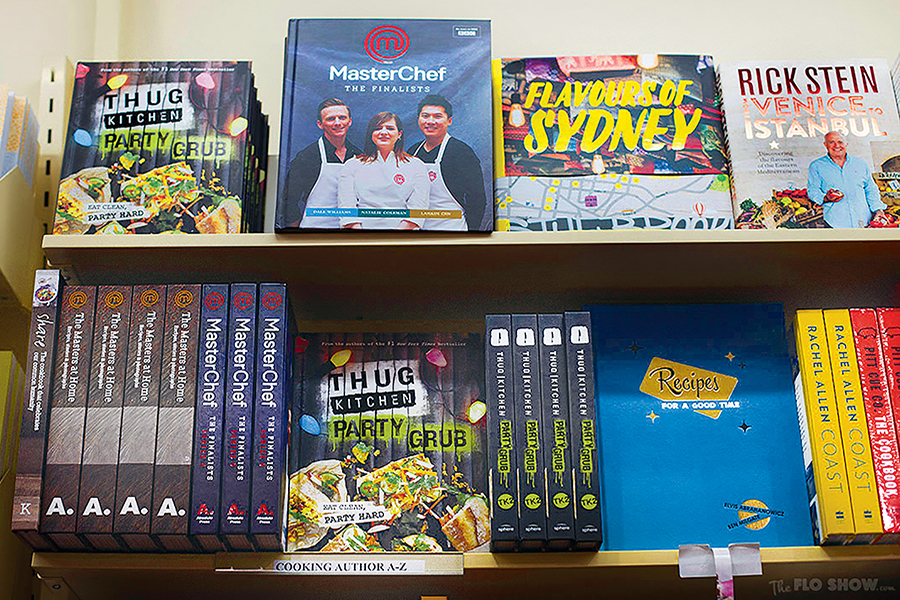

Publishing companies have followed with more spin-off magazines and cookbooks appearing on the market each year. Cookbooks, in general, are actually becoming one of the strongest performing segments in what has been a struggling industry.

The fact that the show has been so popular is a reflection of the increasing sophistication in our culinary desires – desires that have been in no small part created by MasterChef’s extraordinary influence. Melbourne based anthropologist, Dr Isabelle de Solier describes the skills and cultural knowledge that audiences learn from television shows like MasterChef as ‘culinary cultural capital’ – the ability to read and understand the cultural codes surrounding food. Rather than simply teaching us how to cook, MasterChef teaches us about a food culture that was previously untouchable without a great deal of economic and cultural capital. And it is making that cultural capital more accessible to the wider population.

“You can’t pull the wool over Australians’ eyes anymore,” points out Rhys Ward of The Sydney Cove Oyster Bar, as today’s customers are more knowledgeable on what is good than ever before and they have certainly become more demanding when it comes to food quality.

Going gourmet

Research shows that MasterChef is “widening the palates of Australian consumers” and that our love affair with cooking and eating out will continue to grow in the next few years. And as shoppers are expanding their dining and cooking horizons, from the highest quality charcuterie and artisan cheeses to miso and kimchi, the trend and demand for gourmet and exotic foods is flourishing.

To cater for this fast growing clientele, a generation of new fine food purveyors has emerged, looking noticeably different from the poky shops of years past. The new generation has retained the brown paper bags but opted for uncluttered formats and architecturally designed interiors. But it’s not just specialist shops thriving, major supermarkets have been going upmarket steadily for the past five years, with the industry expected to grow largely due to rising demand for premium food products, according to the latest IBISWorld report.

We are also seeing a dramatic change in the layout of supermarkets, making them look more like a food market hall and less like a supermarket you want to get out of as fast as possible.

Retail researcher Michael Bate from Colliers International firmly believes the rise of the celebrity chef and the huge popularity of shows such as MasterChef have forced supermarkets to provide better produce and rethink the long-held cookie-cutter approach to supermarket design with the same product lines in every suburb.

As the public demands more, from the specialist butchers and pastry chefs to cheese and salumi bars, luxury is finally filtering down to the grocery aisles!

The rise of the foodie

Attitudes to eating out are clearly changing. Not that long ago, mum and dad going to a restaurant was a bit posh, a bit of an event really, but nowadays dining in a restaurant is an integral part of family life. The fact that we are dining out at eateries with different cuisines much more than only ten years ago speaks volumes about our ongoing obsession with food and gourmet culture. With TV cooking shows, the influx of food blogs and our generally increased exposure, it’s almost a matter of pride for many people to visit the latest restaurant or that tapas bar before their friends.

Kids are going gourmet too, swapping fish fingers for lobster, sausages for sushi and cordial for coconut water. One-third of NSW children prefer fine dining over fast food and an eye-popping 49% have dined at a chef hatted restaurant at least once, a new survey for online reservation service OpenTable has found. And they are not eating fish and chips either, with 75% of Australian parents saying that their kids are foodies who prefer to eat scallops and macaroons from the grown up menu, rather than picking from the children’s options. John Fink, of Fink Group, whose restaurants include the three hatted Quay and The Bridge Room, said he was seeing an increase in children of all ages eating at his establishments with their parents. The popularity of MasterChef has “changed everything, hands down”, he claims, and since the show first hit our screens, the nation’s young Australians have developed a unique fascination with good food and restaurant dining. Fussy eating now has a whole new meaning!

- Pasadena Foodland, Adelaide

- Pasadena Foodland, Adelaide

Casual by design

Until only a decade ago, if you wanted to have a special meal out, you had to go to a fine dining restaurant but now gourmet is no longer a niche, it is fast becoming mainstream. We are seeing a new breed of quirky, often-diminutive, neighbourhood restaurants where the music is turned up loud, the tables are packed tight and, most importantly, the food is exceptional. Food critics argue that people are moving towards more relaxed restaurant settings, but that’s not to say people don’t appreciate quality; instead people expect more. This is not just about the democratisation of food culture, and knowing what and how to eat, but also embraces a widespread focus on the food production and preparation, on natural, sustainable and healthy ingredients and delivering catering to a global customer rather than keeping the offering too niche.

One great example of the global democratisation of fine dining is the hugely successful Time Out Market, an original concept by Time Out magazine that creates food and cultural experiences based on editorial curation. First launched in Lisbon in 2014, Time Out Mercado da Ribeira is a 75,000ft2 market that brought together some of the city’s top food, drink, art, and shopping offerings under one roof in a cross between a market, food hall and plaza. The market was an overnight success and became the go-to destination for gastronomy and culture in the capital, among Lisboans and tourists alike, and with more than three million visitors it became a number one tourist attraction in the city on TripAdvisor in its first 12 months. It is an example of what CEO Didier Souillat, calls “the democratisation of food and fine dining” which is the underlying and ever-increasing trend to which he attributes the success of the Time Out Market format.

- Time Out Market, London

Time Out Market is unlike other food halls, it is not a street food market, Souillat emphasises. Rather, it is a collection of top quality, expertly curated eateries with the aim to make high-quality fine dining affordable and accessible for all.

It plays into this “desire by people to eat in a social, vibrant and communal environment and to eat what they want to eat, but with proper glassware, crockery and cutlery”, Souillat adds.

Their business model is quite unique, where tenants take a one-year lease and pay a percentage of takings but have no capital expenditure commitments as all infrastructure costs are paid for by the market. The flexibility of the model means the offer does not stagnate and they are able to always offer what’s new, what’s relevant and what’s hot in a city. Following its success in Lisbon, Time Out is opening another branch in Miami this year, with London, New York, Sydney, Berlin, Dubai and Shanghai all rumoured to follow.

- Time Out Market, London

Democratisation of fresh and healthy

In the US, like Australia, until now, the way consumers eat and their access to quality, healthy food has largely been determined by economic status. Basically, those with higher incomes eat higher quality, fresher food while lower incomes mean lower quality and more processed foods. However, things have been changing since Amazon is said to have “sent a shockwave” through the grocery industry last year when it took over high end grocery chain, Whole Foods Market.

A leader in the distribution of high quality and organic food in the US, Whole Foods was also dubbed ‘whole paycheck’ because of its expensive products, but Amazon has acted quickly to shed that overpriced reputation.

While Whole Foods reinforced the fact that organics and premium food were, for the most part, exclusive and for the elite, experts argue that the Amazonification of Whole Foods is making room for the democratisation of fresh and healthy produce. The day the acquisition went through, prices of many Whole Foods staples immediately dropped by up to 40% and an identical basket of items went from $97.76 pre-acquisition to $75.85 only one day post-acquisition. “We’re determined to make healthy and organic food affordable for everyone. Everybody should be able to eat Whole Foods Market quality,” Amazon said in a press release.

- Lockers at Whole Food Market

- Amazon Now Delivery at Whole Foods Market Lamar in Austin, Texas on February 5, 2018.

- Echo Display

Amazon is essentially about merchandising convenience but there’s a broader strategy behind drone-delivered kale. Since the acquisition, the company has been adding its own concepts and services into the fresh food retailer, including price cuts, integrating Amazon technology and opening staffed pop-up stores inside the stores, giving customers the chance to test products before buying. Amazon Lockers are being rolled out in stores for customers to stop by and pick up their Amazon purchases and they’ll probably buy some groceries while they’re at it.

Amazon has already revolutionised the distribution of music and books and it’s also likely to revolutionise food distribution. According to analysts, it has a business model and the logistics expertise, so when you combine its delivery infrastructure with Whole Foods’ 450+ stores and organic food supply chain, you enable the delivery of natural and organic foods to most places in the US in a matter of hours, solving the problem of “food deserts” by allowing healthy food to reach a much wider audience, and at lower prices. Amazon’s intent to make Whole Foods’ products more affordable will democratise organics, claims Forbes magazine, by making it possible for many more consumers to make fresher, cleaner choices. And that is a game changer.

- Coles deli, Southland, Melbourne

- Coles deli, Southland, Melbourne