Online retailing isn’t that good for the environment. Every second, the equivalent of a truckload of clothes is burned or dumped in landfill. In the US, up to 30% of online purchases are returned; the figure for bricks-and-mortar stores is 8.9%! This article by Yaara Plaves and Rebecca Antos of Hames Sharley is featured in the latest edition of Shopping Centre News.

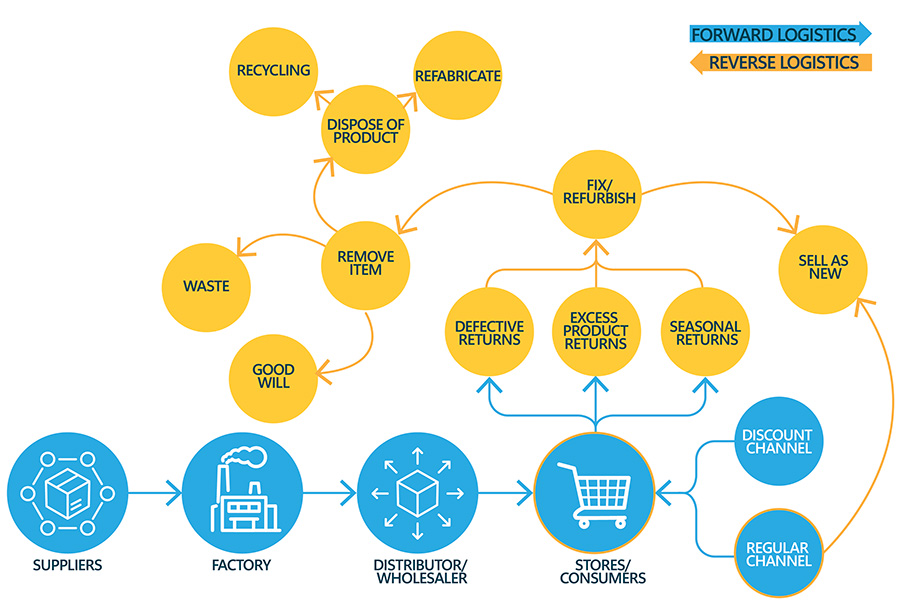

As designers, we create retail centres that deeply consider site, context and sustainability to deliver a return on investment for our stakeholders. But many retailers, especially online retailers, are experiencing a fresh challenge – waste around returnable goods – and with it, new opportunities across the retail economy to refine what we do and how we work to bring us closer to zero waste. One solution is to optimise ‘reverse logistics’.

An issue of scarcity

During the Industrial Revolution, our material possessions were precious. Consumers bought once, bought well and reused their belongings because they couldn’t afford to throw them out. Today, that circular philosophy has been replaced by 21st-century consumerism and convenience, which goes hand-in-hand with waste. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, every second, the equivalent of a rubbish truckload of clothes is burned or buried in landfill. BBC Earth reports that more than five billion pounds of waste is generated through returns alone. Of that, only 20% is defective. For many businesses, it’s simply cheaper to send products to landfill than to keep them in the supply chain.

As we know, our resources are finite. Sand, glass and cement along with oil and copper, are no longer hundreds of years away from running out but more likely within 20 to 50 years.

Our opportunity is not only to go back to the circular philosophy around materials and construction, but also to apply the thinking more broadly to the entire supply chain, from transporting, shipping, freight, processing and packaging the returned goods.

Used clothes at recycling utility in Germany. Image: Lea Rae

In the US, recent data reveals that up to 30% of all online purchases get returned, whereas just 8.9% of goods are returned to bricks-and-mortar stores. This is a great win for bricks-and-mortar retail indeed. E-commerce can plausibly partner more actively with bricks-and-mortar retail environments to help address this gap.

The current opportunities

Encouragingly, we’re seeing retailers around the world take positive steps through reverse logistics. In the US, Amazon has created Amazon Style, an in-store experience and central bricks-and-mortar location for its online range, allowing consumers to meet, have coffee, try on clothing and then either purchase items or leave them behind, with an easier process for returned items. Otherwise known as typical bricks-and-mortar retail, this approach addresses Amazon’s reverse logistics in a traditional fashion while growing and leveraging its e-commerce horsepower. You can still shop and buy online, whether you are in-store or not.

Amazon Style combines the in-store experience with its e-commerce platform. It will be interesting to watch how Amazon’s returned goods percentages compare with the introduction of this concept.

Amazon Drop off returns area in a Kohl’s department store

Amazon’s online retail has also tackled the challenges of reverse logistics by introducing the concept of ‘Return Pallets’ – rather than the complicated process of putting returned goods back into the online sales cycle, returned goods are examined and then placed into crates that can be purchased by consumers. The catch is that buyers don’t have a choice of what is in the crate – a lucky dip if you like. These crates range between $100 – $5,000 per crate and have created a new opportunity to effectively move returned goods on through a less complicated route.

It is exciting to imagine the opportunity for this ‘lucky crate’ concept to develop in our local shopping centres. But how might it work? With the ever-increasing opportunities to grow mixed-use outcomes for our retail assets, we imagine distribution and logistics have a significant opportunity to becoming part of the mix moving forward.

- Image: Kraken Images

- Image: Gorodemkoff

What can we do?

A lot of vacant space is being left behind across the retail landscape due to the downsizing of our large department stores, retraction of discount department stores and the ongoing optimisation of discretionary retail stores. The other important consideration for mixed-use is the role and location of distribution facilities – not necessarily the large industrial scale, but rather last-mile fulfilment and distribution becoming part of the mix in some capacity.

With the idea of creating a ‘return crates’ concept for a local shopping centre, the opportunity for reverse logistics at a local scale could be a pretty interesting concept that could potentially provide greater support for last mile fulfilment.

Where to now?

We’ve seen how food waste is being reduced through programs like SecondBite and OzHarvest and we’re encouraged to see many retailers and brands become more ethical around the world. But transitioning from customers to custodians is not easy, nor can it be achieved in isolation. Stakeholders at every point in the supply chain cycle must be responsible, including retailers, consumers, manufacturers, logistical stakeholders – and us as designers.

Reverse logistics is complicated and expensive; shopping centres can potentially provide the platform to introduce a form of reverse logistics as a new use/business. This has the possibilities of drawing another customer segment, whether it be the ‘lucky crate’ or a form of modernised opportunity shopping.

At the end of the day, waste is bad for business. If we can find ways to mitigate this earlier in the design process, we can better demonstrate value economically as well as environmentally.

Retailers that can save waste, reduce emissions and create a better future for themselves and their customers will pave the way towards more connected communities that will help us all thrive in the future.