The world is changing! Inflation has arrived, unemployment is down and wages are on the increase. What has been ‘normal’ for the past decade is now abnormal. Someone’s kicked the table over! What will be the effect of this on shopping centre valuations? Michael Schuh takes us through the various scenarios.

Cash is Back – Thank God!

The absence of alternatives clears the mind marvellously – Henry Kissinger

Kissinger – often hilarious and rarely wrong. However, he never saw what happens when money is free.

The absence of alternatives – a near zero cash rate – skewed capital markets for so long that there is an entire generation of investors who have no idea what inflation means. It also made for lazy investing. That era is now over.

Low inflation (and deflation) meant growth – or the lack of it – could be ignored, because there was no viable alternative in cash anyway, and the real value of a dollar was not being eroded. That has now changed for good. What inflation does do is focus capital on alternatives and income growth.

What could inflation go to?

Probably the single biggest question right now. There are two drivers and both now appear long term. The end of globalisation, while intrinsically inflationary in the long term, is also very good for lower tier employment in Western countries and this means there should be inflation with economic growth rather than stagflation.

COVID creates havoc with almost all economic output. Its affects look like prevailing. Capitalism though is a wonderful thing. High profits often don’t last because everyone wants a piece of the action. This means the logistics and employment supply issues driving inflation will be softened by new supply as business works out new strategies (such as bringing forward tech solutions).

Don’t however forget about the digital age. The digital age is a fundamental efficiency generator and deflator of prices (just look at valuation fees!) – particularly any service that is repeatable – and the digital age hasn’t gone away. So this will continue to undermine inflation; it’s just not as apparent right now.

All investors look through the short term and invest on long-term fundamentals. The US Federal Reserve System is openly aggressive about inflation and this has happened before, when in the 1970s poor old Malcolm got blindsided when Jimmy Carter did exactly what they are proposing now – and raised interest rates until the inflation genie was broken – bringing about a recession there and here no less. Hopefully, (a big ask) they will have learnt their lesson but it means long-term inflation will probably be between 3% and 4% from time to time. That’s the consensus now with US 10-year bonds (as at July anyway) at just under 3% and Australian 10-year bonds at about 3.5% (but the bond market has been wrong plenty of times too).

Consumption and rising interest rates

This means home loan rates must be 4ish or more. There are a lot of nervous ninnies fluffing around on household indebtedness – including me! Without question, residential values will correct 10% to 20%, however that would only bring values down to roughly pre-COVID levels – and wealthy aspirational areas will probably hold up as their buyers are often high equity.

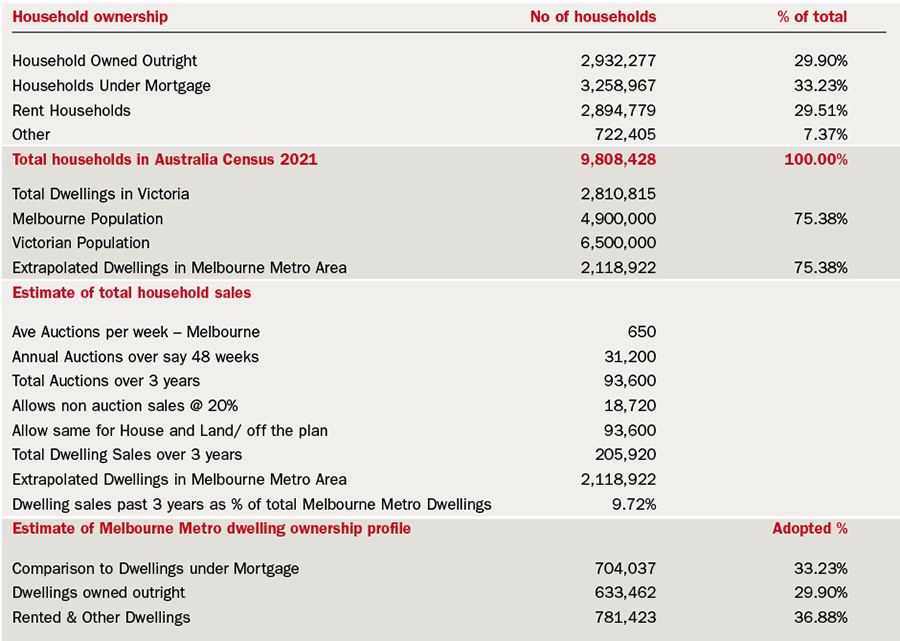

Above is a table looking at the 2021 Census data. It’s a lot of numbers I know, but, at a rough guess, only 10% of the Melbourne households turned over in the past three years when dwelling prices really took off on the near zero (in real terms) interest rates. It doesn’t matter if this is out quite a bit; what this says is that the bulk of the population that own a dwelling either own their home outright or bought it some time ago on lower debt and higher interest rates.

There’s no question that inflation is impacting household incomes but the profile of Australian households says the underlying wealth is there to absorb it. You will all have seen the rather pleasing graph in household savings – which then tells you that maybe the concern on discretionary incomes via the huge home loans is overdone. Without question, consumers’ typical cautionary reaction to bad news means there is some short-term belt tightening but there doesn’t appear to be a serious medium term endemic risk of retail consumption being permanently damaged – and this is outside of wages growth.

Counter intuitive as this may seem, increasing interest rates could prove inflationary. The current inflation is driven by logistics and COVID inefficiencies, not a population spending like a man with four arms. If you raise interest rates materially, and we are at full employment, won’t people demand wage increases, which will then create the wage price spiral they are worried about?

The market is concerned about a recession brought on by central bank rate increases. However, recessions – real ones – don’t often occur when employment is this low. Unemployment rising sharply would require a lot of employers to go broke first, creating a downward consumption spiral. This did occur in the 1990s because business was so highly levered – even one of our major banks nearly went to the wall. The GFC did one great thing – it taught commercial enterprises about the debt trap. While households may be (on historic terms) highly levered, business is generally high equity.

The conditions we have in place make a recession appear unlikely – and particularly unlikely if the government boosts population growth, which seems essential – and there is no better driver for shopping centres than population growth.

Rental growth in shopping centres

Almost every shopping centre lease has been renegotiated in the past five to seven years, so the uncertainty of online penetration on market rents has now largely past and the same can be said of COVID. It’s now also clear that a sole online presence with no footprint isn’t ideal – so store rationalisation has also bottomed as a general rule.

The levelling of the impacts of the digital age on shopping centres has certainly reignited investment interest in the sector but what does the future look like? Rental growth (market rents that is) prior to this disruption followed this old formula: Inflation + population growth + wages growth = rental growth.

Post GFC this looked like this: 1.5% (inflation) + 2% (population growth) + 0% (wages growth) less impact of online penetration (read reducing store footprints) equalled negative reversion.

Post COVID, with the return of normalised inflation – and assuming store rationalisation has now bottomed, and we get our migration going again – shopping centre rental growth could look like this: 3% (inflation) + 2% (population growth) + 3% (wages growth) less impact of online penetration (read reducing store footprints say 3%) = 5%

Ok, that’s a lot! Don’t forget that’s not capital growth, you have to pay for outgoings increases and capex. And the thing about centres is they are all unique – there isn’t a growth factor for the sector you can apply because each centre’s growth is levered to the catchment and its competitors. What this does say, however, is that the rise of inflation adds two new dimensions to rental growth for shopping centres that have been missing since the GFC.

The big societal change we haven’t seen before is ‘Work From Home’. As we already know, this has brought a lot of spending into suburban centres. We’ll have to see how profound this is, but it’s a growth element to suburban shopping centres we’ve not seen before that certainly doesn’t hurt.

Total return focus on growth

Cheap money makes capital lazy. There has been a whole lot of investing with little attention paid to underlying growth fundamentals. But why would you – buy at 5% and borrow at 3% – what could go wrong?

Bond theory is essentially inflation plus sovereign risk. This means cash is now back as an alternative investment class. This means that the “wall of money” in property that has prevailed during the past five years in particular may have an alternative in the next five years. Realignment of capital allocations means the heat of the past few years will probably soften from now on, which wouldn’t be a bad thing. Reducing capital allocations and rising interest rates together almost certainly means softening in cap rates across property, however now enters the importance of growth.

Inflation, and rising interest rates, place income growth fundamentals as central to what will drive cap rates. A short lesson on cap rates though. Just to recap old school virtues.

Capitalisation in perpetuity is the watchword of commercial property. Property, like all other capital investments, is total return driven. IRR less growth equals cap rate; NOT cap rate plus growth equals IRR. In high equity markets, which is what we have at present, the growth outlook, not interest rates, really governs cap rates. Interest rates – as an alternative – play a role in establishing the IRRs though. More on this later.

Rising capital costs (ie. the bond market as the proxy) mean total return expectations for property ultimately will rise. However, this does not mean capitalisation rates rise or capital values will fall because of the growth function. Property is threefold – income, income growth and capitalisation rate.

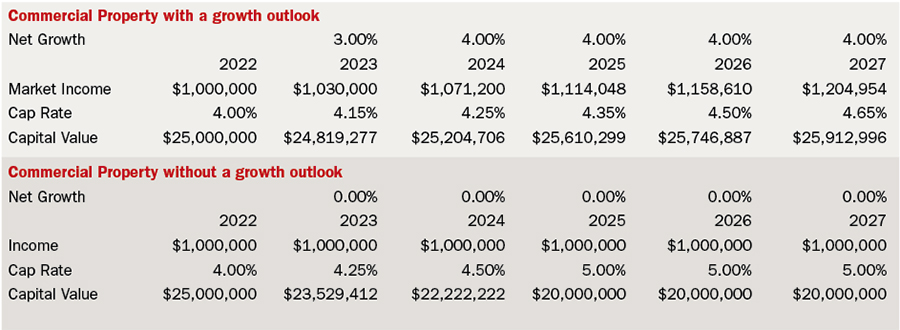

Above is a table that shows what happens in a rising cap rate environment if you have underlying market rental growth and if you don’t.

Yes, the cap rate for the property sans growth, is rising faster than the one with growth. Its old school capitalisation in perpetuity but it’s useful to remind everyone what can happen when the total return button gets turned off. Note how income growth covers up rising cap rates in a capital value sense; and how painful it is if there isn’t any growth.

In a market starved of growth assets, it is very likely that the assets with a growth outlook may see cap rates remain stable, or in some cases even contract. There are a lot of shopping centres that are coming into a growth phase – and a lot that aren’t. We are already seeing huge variations in cap rates and this is the growth function being brought back into play. This can be expected to continue as it’s a return to fundamentals rather than some odd shift because of rising interest rates.

Shopping Centre Cap Rates and IRR Outlook

For a very long time shopping centre IRR’s sat at a general 3.5% to 4% premium to bonds, which is just normal risk pricing against the gilt of bonds which don’t have a capital risk. Post the GFC and deflationary era, the property IRRs didn’t slavishly follow the falling bond rate down. IRRs did fall but at a far more measured rate. This was just no more than capitalisation in perpetuity fundamentals – the property market never believed that the alternative cost of capital would stay at 2%. How wise!

So the premium of the property IRRs (which in turn ultimately drive cap rates because roughly IRR less growth equals cap rate) to bonds blew out to between 5% and 6%. Now, with this sudden increase in bond rates, this premium is at 2.5%. The last time this happened was the GFC. Don’t panic though, we don’t have a credit crisis and highly geared property trusts.

What can we expect?

Well, first we have inflation driving turnover growth and a stable economy. Assuming there isn’t a recession, which doesn’t seem likely, and we get population growth that we desperately need, and wages growth is inevitable, it appears growth for a lot of shopping centre investments will improve.

If IRR less growth = cap rate then an improvement in growth will offset what is likely to be an inevitable increase in property IRRs. For assets without growth, clearly then cap rates will rise, probably significantly. For those with growth – and growth levered to inflation and population, cap rates are more likely to be stable or may rise slightly, however this should be offset by rising incomes.

In a nutshell, the looming change to the market will be a stark demarcation of growth assets versus those without – or those for which there is a great deal of risk to growth and poor underlying demand.

Furthermore, reversionary risk will return as a price factor – an idea that fell away during the low interest deflationary era.

Summary

The return of inflation is nothing more than a return to normal economic conditions. It just feels strange because we have had artificial global capital conditions since the GFC. The outlook for shopping centres looking forward might be something like this:

• The return ofthe bond market as an asset class – most probably when there is some vision on the medium inflation – means that the sea of capital in commercial property and commercial non-bank lending (which granted greater liquidity) – may soften.

• Rising total return benchmarks but very diverse capitalisation rate outcomes (up and down) related to growth.

• Diverse capital value outcomes again related to income growth and intrinsic underlying tenant demand.

• A new period of income growth for shopping centres, even sub-regionals, where they are dominant and have strong catchment fundamentals.

This article was first published in SCN Vol. 40 No. 3, 2022.